Their Tandem Conjoins Unto Fusion

Ralph La Charity

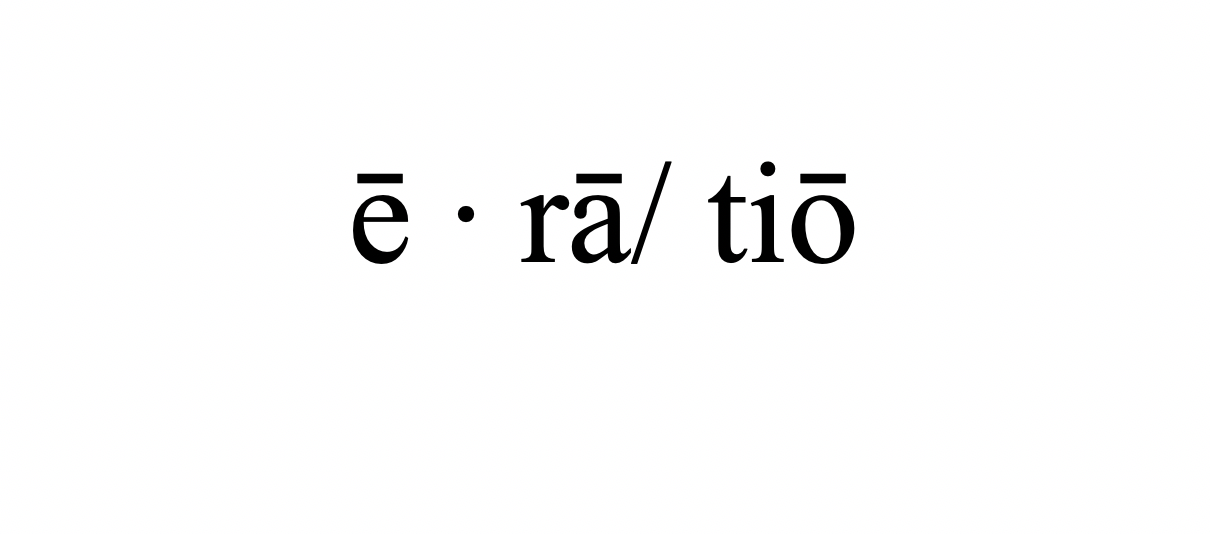

Two poets just published a collabri-libretto that escapes its own velocity, achieving poetry fusion. Evidence for their achievement? Their book, THIRTY-SIX/TWO LIVES - A Poetic Dialogue, just published via Loveland, Ohio’s Dos Madres Press.

One of the two poets, Norman Finkelstein, originally from Queens, New York, is now two years past a bit more than three and a half decades of English professoring at Cincinnati’s Xavier University, a Jesuit institution. Norman has chosen to remain, post-retirement, there in Cincinnati, a secular Jew perforce. The book’s other poet, Tirzah Goldenberg, is a lapsed Orthodox Jew, originally from the Philadelphia Main Line village of Bala Cynwyd. Now in her mid-30s, Tirzah foraged for a time along Front Range Colorado above Ft Collins, where she was living with husband Rico when the Song this book sings was initiated in a back & forth with Norman, via e-mail correspondence (they have yet to meet in person, tho’ they have talked on the phone). Finkelstein is a well-published poet/scholar, whilst Goldenberg has one book of poetry out (thus far), and is represented by Peter O’Leary’s Verge Books, of Chicago.

The last line of each poem in THIRTY-SIX/TWO LIVES becomes the first line of the poem that follows, and the poets take turns as their Song unfolds, for a total of eighteen poems each. Eighteen is a lucky number to Jews, its resonance rooted in Kabbalistic numerology — it represents “life,” so that two times eighteen equals “two lives.” Also of note is the Jewish belief that without the presence of thirty-six “righteous” humans on this earth at any given time, life itself would cease to exist as we know it. Such numerological conjoinments are of pivotal significance — there are no accidents in THIRTY-SIX/TWO LIVES. We are being led to explore what being a Jew might entail — no accidents, but provisional nonetheless, at least with regards to the emerging Song . . .

The book commences with two introductory prose statements, totaling eight pages, in which each poet provides the initiating frame for the poetry which follows, which poetry comprises the whole of the Song’s revelatory emergent fusion. This is the warmest and most inviting of intros to the unfolding that the book tracks, and it serves to give notice to the reader not only that the reader is both welcome and will be cared for, but that the work itself is rooted in utmost self-awareness and devotion:

“The give and take of the poems, the tension of pattern and free expression, the range of Jewish reference (sometimes in Hebrew or Yiddish), are all signs of shared psychic attention. Two lives, two voices, but one poetic totality.” — brief quote/sample from Norman’s intro prose.

“The pandemic had begun, and my husband Rico and I were temporarily living in an isolated cabin in the wilderness, sighting moose far more commonly than people. During this time, Norman and I began a conversation in verse.” — brief quote/sample from Tirzah’s intro prose.

What follows are but two of the thirty-six poems, demonstrating two features: 1/ how the poems proceed by using the last line of one poem as the first line of the following poem, and 2/ how both poets make clear and explain references to specific Jewish language and history in the book’s endnotes. The degree to which such clarifications and explanations in the endnotes are employed is a thoroughgoing discipline the book’s authors adhere to consistently, forestalling any Gentile poetico’s (me) lack of Jewish lore (that the reviewer herein undersigned is grateful for such care is herewith accorded):

Cloven Place

Place of the Revealed

Backside of the God

Omnipotent Trickster

Forever departing

What might it mean

for the countenance

of such a One

to shine upon us?

to serve as the footstool

of such a One?

North of Fort Collins

and in East Walnut Hills

the American Qumran

in glorious isolation

waits to be discovered

(NF)

From the book’s endnotes: Exodus 33:21-23: “YHWH said: Here is a place next to me; station yourself on the rock, and it shall be; when my Glory passes by, I will place you in the cleft of the rock and screen you with my hand until I have passed by. Then I will remove my hand; you shall see my back, but my face shall not be seen.” (trans. By Everett Fox)

(NF)

From the same endnotes: Qumran is an archeological site near the caves where the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered. It is believed that the Essenes, a Jewish sect, lived at Qumran, and that the scrolls belonged to them.

(TG)

waits to be discovered

from Fromm’s take on dreams

Scholem’s Ger Sham

Hasidism’s turn

to the inner worlds

where the ego longs to help the wheel

return to Nothingness

and other books

the body recovers in sleep

the world concealed

the dreamer is led to the silent ponds

a trickster longing for her dinner

a trout beneath her silent silver

Hebrew amulets

upon’s paleographic countenance

mirroring devekut

ripples from the files

of the imminent foundation

immanence immense but subtle presence

when you write me imperceptibly from the depths

You may call me Alanna

(TG)

From the book’s endnotes: Gershom / “Ger Sham,” Scholem’s first name, which he chose in place of Gerhard when he turned more resolutely toward his Jewish heritage, meaning “a stranger there.”

Devekut means cleaving or closeness to God. Devekut “constitutes the very heart of Hasidic thought, teaches man the path of spiritual ascent until he reaches the divine element within himself and clings to it without limit.” (Yoram Jacobson, Hasidic Thought)

(TG)

What these two poems further illustrate is both how down to earth and how arcane these two poets simultaneously are in their allusions and in their vocabulary. Since these two poems occur early in the progression of the whole towards fusion, it is apparent that there is a method of scholarly outreach and inclusivity at work in the poetic sequence from the start: the poets ground themselves in the broadest of inputs, taking heed of both current and ancient touchstones. Said touchstones will become increasingly fluid and evocative as the poetic weave builds towards eventual dynamic unity.

Where was my commons?

it stretched from the Jewish Center

of Kew Gardens Hills

to Goody’s candy store on Jewel Avenue

it stretched from P.S. 165

to the World’s Fair grounds

Flushing Meadows Park

the commons: public good,

public spaces

for children, it goes with saying:

“to be such keen recording instruments

of the microscopic surface

of things close at hand”

simply to be that way

before the onset of nostalgia

before presence becomes memory

wait and I will tell you

(NF)

wait and I will tell you

of observance in its rounds

of the eruv in its orbit

of the fox throughout the town

of the evidence in absence

of the weights and not the loom

wait and I will keep

whichever furniture will keep

iconic

(TG)

From the endnotes: On Shabbos (the Sabbath), in traditional Jewish practice, one can only carry things in a private area. An eruv creates a private area within a public one by enclosing a particular space with something to indicate that enclosure. . . . When the eruv is up, people can, for example, carry books and prayer shawls to and from the synagogue.

Iconic

That word is the first word of the 36th poem in THIRTY-SIX/TWO LIVES. To have gotten as far as the first word of the final poem, a reader will have absorbed a significant number of interpretive endnotes. The labor will have endured and been enriched by poems loaded with lore, personal specifics, echoes innumerable, and clues to prophecy, that utmost of poetics denouements. Prophecy occurred in the sequence’s very first entry, as writ by TG, that entry’s last two lines:

/ the eruv’s up, secure / a fox afoot before the ark’s dark

door / to Torah sing secure / all’s arc’s dark door to Torah

And how do we know that the fusion this review claims has been achieved? TG’s final poem was the one above, her 18th, the one beginning with the line, wait and I will tell you . . . and NF’s final poem, his 18th, ends with these six lines :

So I called you

from the shtetl of my soul

Tabernacle of the profane

and of the sacred common life

Despite everything

the gift of prophecy

So that finally, returning for a last clue, there in the early early intro, a la TG, the clue abides:

“Here in Thirty-Six the communal space in a sense mimics the permissiveness of this private-public/public-private ground; it is a generous meeting-place between poets and friends, an exercise tautened by the limits of each other’s lines. Each line on offer was unfamiliar at first, unmoored, emerging from the moorings of someone else’s mind. But like any text we encounter, a string of words weaves its way into one’s own context and becomes an anchor there for further thought.”

We, its readers, regardless of our specific heritage, get to close in upon that ground by absorbing what is on offer, its fusion being our own enactment engaged, dynamic even in repose, just prior to the onset.

Currently billing himself as a poet in private practice, Ralph La Charity’s first book of poetry was Monkey Opera, published in 1979 as a joint effort by San Francisco’s Bench Press and Kent, Ohio’s Shelly’s Press. La Charity is an Open Poetry adherent across America’s abundant hide, and he still comes up volunteer. His most recent book is Blood Vertigo, 2019, from Dos Madres Press of Loveland, Ohio, which press will publish his eighth book early in 2022.