INK:

An Interview with Artist Thomas Little

by Contributing Editor Coleman Stevenson

Thomas Little of A Rural Pen Inkworks is an artist and ink historian who explores mystic and scientific concepts through the lens of ink and our relationship to mark making. He gathers threads from alchemical imagery, chemical phenomena, and mystic observations, and incorporates them into a holistic synthesis theory of art-science-magic. The natural world informs his work with ink in not only the materials used, but the relationships expressed between plant, animal, and elements. Current projects include creating inks with iron pigments derived from dissolved firearms, as well as art experiments incorporating the Physarum genus of slime molds. He is available to make inks and devotional-art-objects on request. He has lived many places, but always dwells near dark water.

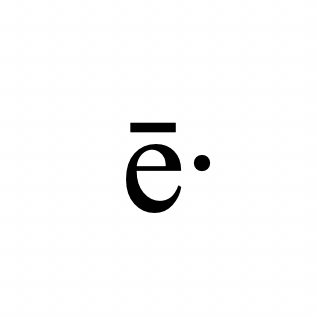

An ampule of Little’s ink against one of his alchemical illustrations.

CS: What’s important to you about living near water? How does that inform your creative work?

TL: Oh gee! I love water. I grew up on the Black River, and riparian thinking has always been a part of my creative process. I like how invisible creatures travel in it, how it brings things to you and reveals ancient hidden things. I used to imagine living in a river was like living in a hallway where the ceiling changes height all the time, and suddenly new doors to different rooms appear. And with dark water, especially, I like to look at the reflections of the topside world. It is like looking in a mirror made of black mercury.

CS: Oh that’s lovely! Reminds me of a video game, how certain gateways are hidden until you have the right element present or the correct vantage point. There can be a lot of patience involved in that sort of waiting for the right moment/alignment of circumstances. Interestingly, a lot of the work you do involves patience because you are waiting for something to happen once you’ve set things in motion (waiting for a gun to dissolve; waiting for the slime mold to move). What does that feel like for you to be both in control and out of control in your artistic practice in this way?

TL: It’s maddening, of course. But essential. We are always caressing unknown boundaries; sometimes we get burned bad by them. That makes even the smallest breakthroughs the best! I love those nodes of intersectionality.

CS: Writers and artists are often very particular about the spaces in which they create their work. While I’ve seen evidence that you can create just about anywhere, how has having a studio (and recently expanding it) changed your work / the way you work?

A wall in Little’s studio.

TL: It’s been nice, a little stressful with the rent increase, but I like to move. I walk a lot! I really don’t like standing still. I pace in circles a good third, maybe more, of my waking hours. Moving clears my mind. It’s about a 4 to 1 ratio of movement to creative “desk” time for me. I’m a lousy statistician though, so that’s an estimate. Ha ha.

CS: How did you first become involved with the slime molds and how exactly did you decide to incorporate them into your creative practice?

TL: I had known about slime molds for a while, and I knew in the back of my mind that they were interesting organisms. They are present in the swamp here, and their bright colors stand out in the somber shades of the deep woods. My interest really sparked in a rather prosaic, and slightly fateful, way. It was a rainy evening in September, and I was watching PBS. There was an episode on slime mold airing, and it was showcasing all the interesting behavior Physarum polycephalum was capable of. On a previous day I had encountered that bright yellow creature on a rotting tree near the river. In the morning, after the rain, I returned to this tree and found the population of Physarum still active. I took a small bit of bark with some on it, fed it some oatmeal, and I’ve been devoted to it ever since.

Physarum is, in a very real way, a living ink. It navigates its space using an external memory. In depositing a mucus trail, it knows not to return to places it has already been, unless it absolutely has to. And as its shape is a record of its behavior, it is essentially leaving behind a diary, or autobiography, of its life. This is perhaps what is most compelling about working with it in my pieces. I did some research about what pigments it absorbed and carried in its cytoplasm, and as fate would have it, some of the best results were with iron oxide pigments, my forte!

There is much more I could discuss about Physarum; it really is a mind-blowing entity, and so much more than a simple “mold.”

CS: As “collaborators” in your work, it seems like they are communicating more than just simple likes and dislikes of the substances you place in their path. Your description of them as “living ink” is amazing; it truly looks like they are drawing or writing on the page. How exactly do you use the Physarum’s ability to carry iron oxide pigments to make your art?

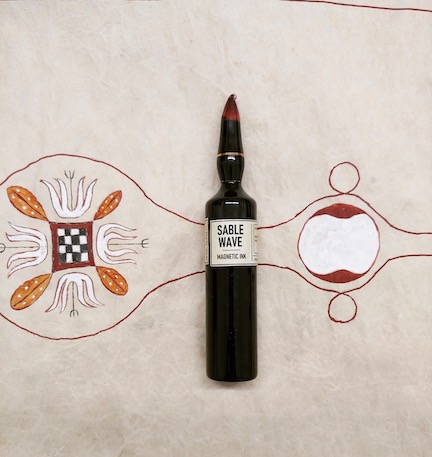

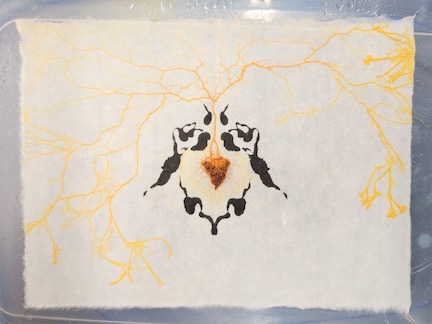

Cauda Pavonis, a finished slime mold collaboration.

TL: My process for making a piece goes accordingly: I create an inkblot using black iron oxide and an extract of valerian root. The valerian root usually is an attractant to slime mold, but my population is anomalous in that it is repulsed by it. This causes the slime mold to want to avoid the black ink. In the middle of the inkblot I place a small cake of oats (slime mold’s favorite food) and red iron oxide. The slime mold will eat the oats, and ingest the red iron pigment, but it will also begin to search for other food sources. As it finds the valerian root extract unpleasant, it tends to avoid crossing over the black ink and will devise a route that involves as little contact with the black ink as possible. Once free from the blot, it begins to fan out in different directions, while maintaining a link to the red oat cake food supply. As this link is further established, more red pigment is deposited, creating vascular shapes on the page.

Slime mold responding to an oat cake.

CS: Are there patterns/recurring forms in their trails that you can read like a text as you become more and more familiar with their movements?

TL: There are some behavioral patterns that emerge, trends in the behavior that I recognize. It will occasionally get wispy long pseudopods if it has marauded for a long time on the page. I don’t know if I am at a stage where I can “read” them, but I do think of it as a kind of discourse. Like, the inkblot is the question, and the slime gives its answer.

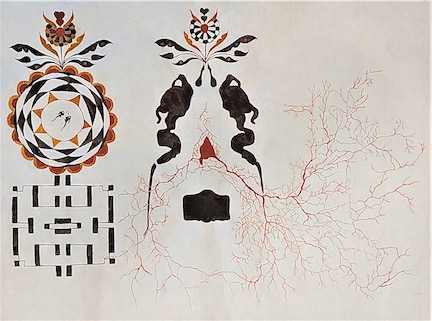

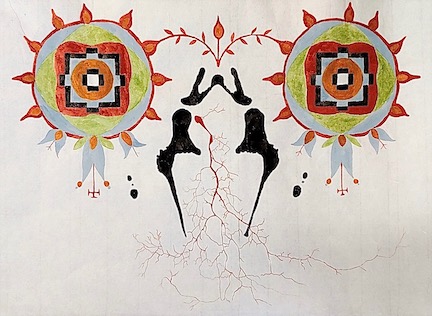

Irgarten, a finished slime mold collaboration.

An untitled slime mold collaboration.

CS: I like that very much: “The inkblot is the question.” In the collaborative inkblot works that you and I have been making this year, that feels right to me, too. In some way I am trying to “answer” them, to interpret them, and then add my embellishments according to what I intuit from their shapes. What has it been like for you to see text and other scrawlings added by another human hand instead of your usual yellow collaborators?

TL: I love seeing your work with the inkblots! And I think part of the reason is that your use of text is more structural, more like a graphic component. Inkblots are interesting to me in that they exist in a strange plane until meaning is attached to them. Once an image is seen, it is that image, and the ambiguity is gone. I try to make my inkblots, much like Rorschach, exist in a place that straddles familiar images and inscrutable but compelling shapes. When clustered together they take on the qualities of a word or paragraph and become a kind of asemic alphabet. I think your treatment of text and my inkblots intersect at this point.

An inkblot by Little embellished by Stevenson.

CS: When you’ve included text with your inkblots in the past, it felt . . . more diagrammatic maybe? Tell me more about those pieces.

TL: Oh yes! That was a kind of theoretical anatomy. I was identifying different parts of the inkblots. That was a fun exercise.

.jpg)

One of Little’s diagrammed inkblots.

CS: Tell me how you first came to make ink out of an old gun. What was your motivation? How has this project grown since then?

TL: When I first started making ink, I was interested in older recipes. Iron gall ink was what I made back then. I’ve always had a resourceful streak in me, and I wanted to make ink from what I had on hand. Oak galls were plentiful, so I needed an iron source. My father was a gunsmith in his early years, and we had lots of odds and ends of gun parts laying around. It seemed like a powerful source to make ink out of. I lost a very close friend to gun violence and have been on the other end of a gun. They are a constant source of loss, helplessness, and grief. Their power to render people voiceless, either through fear or outright murder, is a great spiritual irritant to me. Transmuting them into ink I feel is a step towards expiation. While ink can be weaponized, at least it requires a quality of finesse that the brute finality of a gun eschews.

A handgun dissolving to make ink.

I’ve been making ink out of guns for at least six years now, and it has afforded me alliances with projects that are of a kindred nature. Lead2Life is an organization that makes guns into shovels used to plant sacred trees in places that have been affected by gun violence. They take the “swords to plowshares”' concept more literally than me, ha ha. I help support their work through the Wild Pigment Project, another great organization, which seeks to remediate violence against the earth, in all its sad and various forms, through education and practice regarding natural pigments. These and other opportunities have come about through what I’ve been doing with guns.

Ampules of finished ink.

CS: As an ink maker, do you think about what your inks will be used for while you are creating them? Do you have any hopes for how they will inspire other artists and writers?

TL: I do think about what my inks get used for, and even get so lucky to see what others make with them. A lot of people use them in ritualistic pieces, which I am greatly flattered by. Some people ask me what sort of ceremonial things I would recommend doing with them, and I tell them whatever! Ha ha. In terms of magic, the heavy lifting has already been done. A weapon is now ink. The rest is icing on the cake.

As far as inspiring others, I at least hope that it makes them think about where their materials come from. I make my pigments from murder weapons, but I’m sure more violence is perpetrated by the petroleum industry that provide many of the products artists use on a regular basis. Sometimes though, when I’m making a blot or doodling, I forget that I’m using material that used to be a Smith & Wesson, and I kind of like that. The weapon that steals voices has had its own identity erased, anonymized. A kind of damnatio memoriae of artifacts.

CS: It sounds like you consider your process of making ink to be a ritualistic/spiritual practice. How does language factor into that? Do you have any utterances/incantation that are part of your process?

TL: I do think of it as a kind of spiritual practice. Or at least a kind of metaphysical one. I lean towards the alchemical persuasion, and I do think of it as doing the Great Work. But I don’t see myself climbing a ladder—more like walking in a wheel. As for language, I try to keep it out of my process as much as possible, certainly in the formation of the materials, and only in nascent form in my finished works. I love words, etymologies, histories in letters, but I also know that they are tools that really hide the mysteries of the world from us. Like with all artifice, it can approach the great unknowns only tangentially. I like to bring the mystery into the scope of the viewer, but I prefer them to focus on whatever content it may contain for them. I like white noise when I work. Sometimes I use a rattle to clear my head. But mostly I like silence. The world is so very noisy.

Two inkblots with Little’s handmade rattle, crafted from river cane, sparkleberry twig, a crossvine seed pod, and river pebbles, with a kombucha-leather handle.

All photos are from the artist. Learn more about Little’s work on Instagram at @a.rural.pen.

Little, Stevenson, and artist Candace Jensen will launch a 3-person show in May of 2022 at Amos Eno Gallery in Brooklyn, NY. Their collective works will explore the chimerical realm of language + visual symbolism.

Coleman Stevenson is a contributing editor at ē· rā/ tiō.