The Bob Grumman Interview

This

interview was conducted by way of an exchange of e-mail letters

over the course of October, 2002 to January, 2003.

—Gregory Vincent St. Thomasino

Gregory Vincent St. Thomasino:

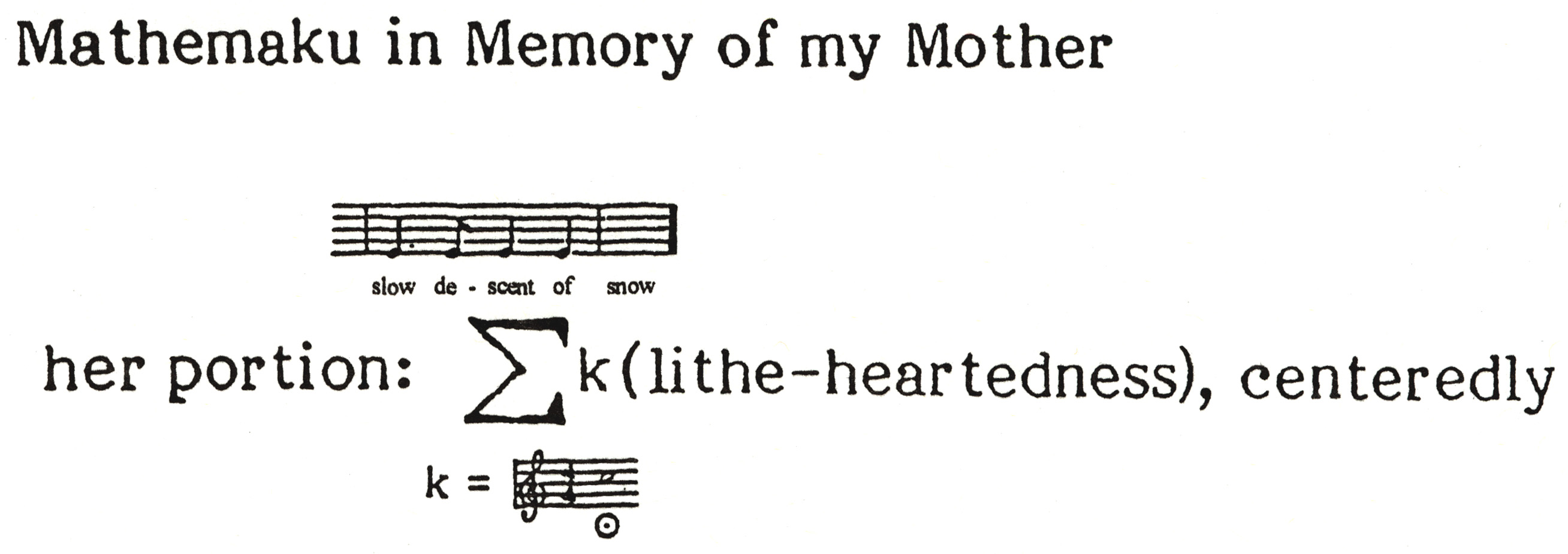

About "taxonomy" (by which I mean, the laws and principles covering the classifying of objects) and "nomenclature" (simply, the system of names), when I mentioned to you my preference for the word "eidetics" as a general terminology to cover concrete and visual poetry, you asked me for a formal definition of it; so here it is (and I've taken this from Peter A. Angeles' Dictionary of Philosophy; it is not a neologism and I have not given the word a new meaning; when I use the word I mean it in this sense): Eidetic (Gk., eidos, "that which is seen," "form," "shape," "figure," "appearance"). Referring to an idea or image that resembles the characteristic property or constitutive essence of a thing.

That's it. Now when it comes to visual poetry (inclusive, of course, of the "typewriter poem," of "concrete poetry," and of, say, Apollinaire's "calligramme"), I then have certain requirements: The piece must present two aspects; it must show as well as tell. And these two aspects must complement each other, the one completes the other, but such that 1) the one is inherent in the other, and 2) they together enjoy a synergetic, a cooperative relation (in that the total effect is greater than the sum of the parts).

Now according to my terminology, a lot of what I see passing as visual poetry is not exactly visual poetry, but is, rather, for instance, collage, calligraphy, graphic design. . . . It's gotten difficult for me to justify the use of the word poetry in the term "visual poetry"—but while, sure, these pieces have here and there something "poetic" about them (in that, say, the juxtaposition of the elements might be subtly or symbolically suggestive); still, to be "poetic" is not synonymous with poetry, and to be "visual" is not synonymous with being complementary. It seems to me this visual poetry is very far removed from its roots in poetry and in the typewriter poem (and indeed in the carmen figuratum, and prior to that in the Pompeian Paternoster). Now I'm all for the evolution and modulation and transition, and even transposition, of a genre form—ergo my introduction of the term "eidetics," via which I mean to be inclusive of these developments—but I do not think these roots have been tapped dry, and I think a certain discipline has been abandoned.

So where have I gone astray? Would you tell us, how should we think about visual poetry, and so as to gain the greatest appreciation of it; and can you give us a formal definition of visual poetry, using your own nomenclature; and would you trace for us its history back to the typewriter poem, or to wherever you think its roots have their ground?

Bob

Grumman:

You first define taxonomy as "the laws and principles covering the classifying of objects." For me, taxonomy is the systematic classification of objects. You then consider nomenclature to be "the system of names," which made me think about the fact that I do try to make up a terminology that is systematic—whose terms, that is, not only appropriately name things, but interrelate: e.g., I use "equaphor" as my general term for "figure of speech" or "trope," thus connecting it systematically to such specific equaphors as the metaphor and my "juxtaphor."

I like the word "eidetics," by the way, but don’t see how it covers visual poetry.

You and I agree that visual poetry "must," as you put it, "present two aspects; it must show as well as tell. And these two aspects must complement each other, the one completes the other, but such that 1) the one is inherent in the other, and 2) they together enjoy a synergetic, a cooperative relation (in that the total effect is greater than the sum of the parts)," but we are in a minority in the visio-textual art field in that. I feel that a visual poem should have a graphic element which fuses with its textual element—and, as you suggest, completes and is completed by the latter.

Your contention that "a lot of what (you) see passing as visual poetry is not exactly visual poetry, but is, rather, for instance, collage, calligraphy, graphic design" which makes it "difficult for (you) to justify the use of the word poetry in the term ‘visual poetry’" made me think of recent conversations I’ve had with Scott Helmes over whether some of his atextual work is visual poetry. He has interesting arguments on this about how some atextual pieces can be "read" as though they were texts and therefore can be described as poetry. Such pieces can’t be simply looked at, but must be linearly scanned. They usually form some kind of narrative. I’m still considering the matter though holding to my dogma of many years that a work has to be textual, even semantic, to be considered a poem.

"Still," to quote you again, "to be ‘poetic’ is not synonymous with poetry." Right. When discussing taxonomical questions, we need, I believe, to discard terms used . . . equaphorically. That many poems are "sheer music" does not make them literal music, for instance. I see little point in using the term "visual poetry" to represent a lot of the atextual material some have represented it with, except to give that material some kind of high-art veneer. This is what comes of a terminology’s being misused to judge rather than neutrally describe. "That’s not poetry" being the standard sputter of the Philistine instead of "That’s not good poetry." The proper answer to that, for me, is to show how the work is poetry, by some objective definition, unless it is not, in which case, the proper answer is, "So what? Whatever it is, it’s aesthetically effective."

When it comes to defining "visual poetry," I’m not quite ready to tell anyone how we should think about visual poetry, but am willing to say that I do think my way of thinking about it makes more sense than any other way I’m familiar with.

My definition starts with Verbal Expression. "All verbal expression, oral or written"—and now I'm quoting from an essay I have on the subject at my website—"can be split into three main varieties, according to its purpose: Literature, or the use of words in the pursuit of Beauty; Informrature, or the use of words in the pursuit of Truth; and Advocature, or the use of words in the pursuit of Goodness (or, more specifically, the Moral Good)."

I’ll skip, for now, how I distinguish poetry from prose to jump to what I call "visio-textual poetry." This consists of (a) visual poetry (poetry containing visual elements that are as expressively consequential as, its words), and (b) visually-enhanced poetry (poetry written in an elegant calligraphy, for instance, or with letters that look like trees or people or the like, as in illuminated manuscripts, or in any manner that increases the work’s ability to please but does not increase its core meaning.

There is also something outside literature, in my opinion, that I call "textual illumagery." It is illumagery (or visual art) that contains text without semantic meaning, or whose semantic meaning is irrelevant to the central meaning of the work, as might be the case of a cut-out of a human figure from a newspaper, for instance, if the only significance of the newsprint is to establish some kind of newspaper tone.

In the glossary of my book, Of Manywhere-at-Once (v 1, 3rd ed), I say visual poetry is "poetry whose visual appearance is as important as what it says verbally." I'm more exact on page 138, defining visual poetry as "that which results when the visual appearance of some portion of a poem’s textual matter contributes significantly to the poem’s central expressive value." This latter may be my hundredth attempt to define the term. In my book I spend several pages discussing my struggle to do so.

Now that I reflect on it, I see I should have said a visual poem was "that which results when the visual appearance of some portion of a poem contributes significantly to the central expressive value of the poem’s text." The problem is trying to make the point that making a visual poem is more than simply putting textual and graphic material on the same page. On the other hand, the graphic part need not physically fuse with the textual part.

No, it has to! But sometimes the interconnection can be carried out by negative space. Dotting a lower case i with a smiley face, for instance, would make the i a (trivial) visual poem, although the dot was separate from the rest of the i—because, for me, the white space between the dot and the body of the i would fuse the two.

This is a difficult-to-discuss area, but I hope my general slant is now apparant. Before going on, let me give my 102nd definition of visual poetry (and the 23rd final definition of it): "that which results when the visual appearance of some portion of a poem that is part of, or clearly integrated with, the poem’s text, contributes significantly to the central expressive value of that text."

Obviously, there are three potential areas of contention in this definition—spots where subjectivity is unavoidable, that is (and no definition is free of such spots): what constitutes clear integration, how does one judge the significance of the contribution of the visual appearance I speak of, and what is any text’s central expressive value." I can only say that in most cases, a consensus of informed readers will fairly readily agree on the answers to all three. In the cases where they do not, the definition will at least aim someone trying to determine the identity of an artwork at its most salient features.

Now, to go back to your set of questions, I would say that to appreciate a visual poem, you should just read it as attentively as you can and look at it with equal attentiveness—and bring as much of your knowledge of poetry and illumagery to it as you can. As for the history of visual poetry, I’m no expert, though I’ve tried to study as much of it as I can. My impression has always been and remains that serious visual poetry did not start until Apollinaire. Before that, there were isolated poets who made interesting visual poems, but very few that I know of who did more than shape poems to show ingenuity as opposed to achieve any significant equaphor (and I tend to believe any genuine visual poem will combine its graphic and textual elements into an implicit metaphor of some kind—a visiophor, in my terminology). Spelling "Jesus Christ" so that "Jesus" goes across the page and "Christ" goes vertically through "Jesus" was a lot more than cute when first done, but is still too primitive for me to count as a full-scale visual poem. Ditto the shaped poems of Herbert and others. I feel Apollinaire got visual poetry started toward true high art, and Cummings contributed significantly to its development, followed by Patchen, and the concrete poets like Grominger. The first generation of American visual poets consisted of Ronald Johnson, d. a. levy, Aram Saroyan, Emmett Williams and their comrades. In the next generation were Karl Kempton, Karl Young, K. S. Ernst, Marilyn Rosenberg, Scott Helmes and their comrades. A third generation would include people like Crag Hill, Geof Huth, and me (though I am older than many of the people in the second generation, since I’m going by entrance dates, not age).

All this is a very rough view, off the top of my head. The only thing I would stand by is that visual poetry did not come into its own in this country, in spite of many gifted fore-runners, until around 1960. It seems to have had two peaks—one around 1965, the other from the late eighties into the nineties—and about to have a third, on the internet.

But even if it is "aesthetically effective," the question is not only is it or is it not poetry, but was it intended to be poetry, for if it was intended to be poetry, and failed, well, that seems to be a whole other judgment from is this effective as "visual poetry." Wouldn't you agree? This is not to suggest that visual poetry must be poetry (in the sense of, say, Blake's "Tyger," Yeats' "Leda," Apollinaire's "Il pleut") in order to be art. I think you're right ontarget, that we need to avoid using terms equaphorically. And, providing the aim of "visual poetry" is not to necessarily be poetry, it still has its own aesthetic criteria to follow and to satisfy. But hasn't "visual poetry" already managed to separate (divorce?) itself from poetry, into a field of its own (and for which I would suggest the term "eidetics"), a field you have been charting and demonstrating the legitimacy of? Would you say visual poetry is still in its grass-roots stage, or has the internet begun to change that?

I'll

just say here that if a person intends to make what he thinks is a visual

poem, and it fails to satisfy my criteria for visual poetry, I will

judge it not a visual poem without necessarily judging it not

a first-rate work of art. To me, an artist's intentions beyond

their manifestation in a given work are irrelevant except as possible

guides to appreciation.

I agree that visual poetry need not be "poetry (in the sense of,

say, Blake's 'Tyger,' Yeats's 'Leda,' Apollinaire's 'Il pleut')"

in order to be art, it only needs to adhere to my criteria for the form.

I believe that visual poetry certainly has divorced itself from other

forms of poetry, as traditional free verse poetry (in my taxonomy, "plaintext

poetry") did before it. I don't see it as having left "poetry"—which

is why I reactionarily require it to be semantic, like traditional poetry.

I feel visual poetry was in its grass roots stage till the middle

of the century just past. I think it is now in its prime, with

most major workers in the field—in this country, at any rate—adding

color to what they do. Of course, that may be only because I have

only begun doing that myself during the past few years, and am over

enthusiastic about it. Still, I think visual poetry got far beyond

the grass roots stage by the late eighties. I think animated visual

poetry is at the grass roots stage now, but will take off—is taking

off—on the Internet. I see that not as further growth of

visual poetry but as almost a different artform—the way, again,

plaintext poetry broke off of what I call "songmode poetry,"

or traditional metrical, sometime-rhyming verse. Work on the Internet

is also extending various static burstnorm forms in ways I don't yet

have a handle on—though most of the work I've seen on the Internet

is pretty lame, and uninnovative, however much the poets seem to think

they're in new territories. There's a lot of Neo-Cummings out

there, for instance.

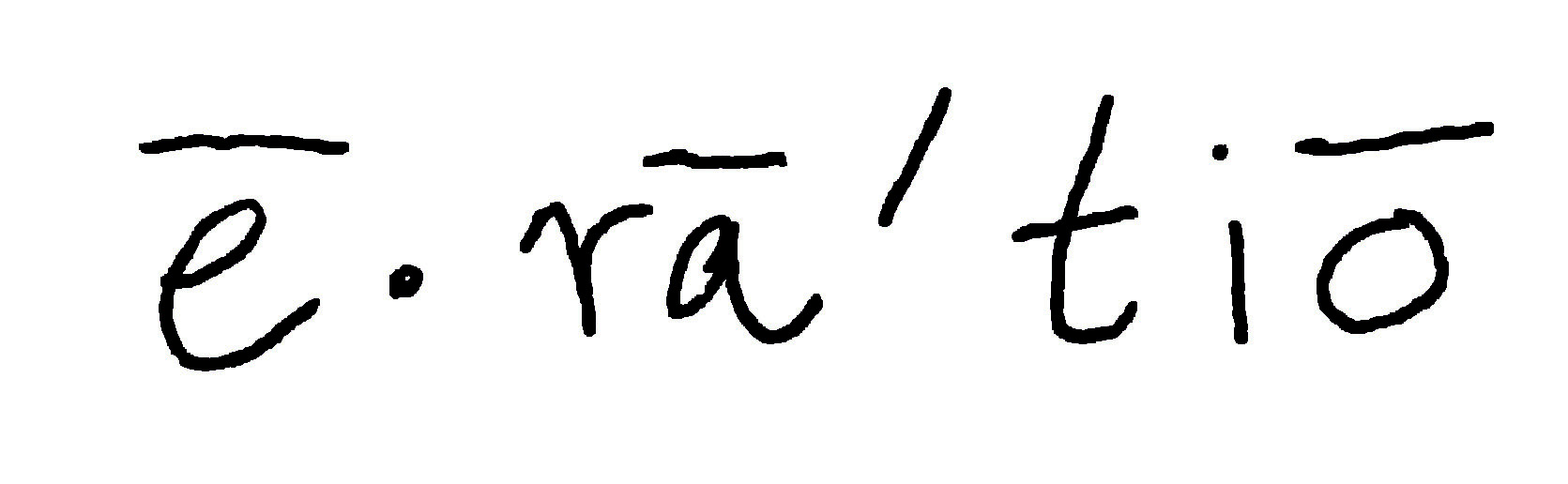

In your commentary on "Mathemaku No. 10"—at your website, Comprepoetica—you make reference to "the tension between open-ended verbal generalities and closure-seeking mathematical strictness." (And not only strictness, but "succinctness"—and also in regard to closure-seeking mathematics.) These are essential and distinctive characteristics: strictness, succinctness, closure-seeking. They denote specificity. I now want to interpret this to say, the tension between the general and the specific. This tension is desirable for you; you describe it as "the arithmetic of the poem happening, the machinery of the long-division specimen chunking smoothly and inexorably along, and—almost ridiculously—making poetry." (And probably we can substitute uncannily for almost ridiculously.) You next make reference to what is perhaps your most intriguing idea: "To put it another way, I feel myself to be simultaneously experiencing the poem in two distinct places in my brain, the mathematical and the verbal. To get a person into two (or more) places in his brain at once is, to me, the highest function of poetry."

I'd like to venture an interpretation of this tension (since you don't give us one, and since as with so many of your ideas, the things you say in support of them are as intriguing as the ideas themselves). I interpret this tension to be the sign of a precipient intuition insisting to be resolved (articulated, depicted), but whose resolution (whose culmination) must take the form of an intermediate idea (nay, of an abstraction taking or disclosing to you its potential sensible concretely perceptible form). The intermediate idea is the mathemaku, and indeed it is each discrete factor in the agreement of the division.

As for my use of the word intuition, I admit, it is convenient, but where there's smoke there's fire, and tension seems to me to be an effect, in which case I want to learn the cause; would you comment on what this cause might be, and on its relation, its connection to poetry? (I am tempted to venture the poem has a tension-quotient, and this in proportion to the problem—or, "the thrill of solving" that problem—that it poses.) You maintain that your reader, the "aesthcipient," can experience this tension for himself (if maybe only as "the thrill of solving" the mathemaku) as he reads, both mathematically and verbally, the division in the poem; and thus you put your reader into two distinct places of his brain at once. This is quite a challenge, for both poet and reader. Would you explain this (or, what about it should we take literally and what should we take figuratively)? And would you tell us, what is an "aesthcipient"? Is he at all like Kristeva's "reader of intertextuality"? And please, how does one become an aesthcipient?

Poetry is not a totally intellectual experience (actually, I don't think I've ever had a totally intellectual experience); a poem can be evocative of a sentiment—and certainly a poem that asks us to multiply poetry by a hand-drawn heart (and where that heart may stand as a synecdoche for the whole of one's desires). "Mathemaku No. 10" seems to be one of your most intimate poems; can you tell us something about your relationship with your poetry, for instance do you find yourself in conversation with your poem, and, if I may, is poetry the form you give to your desires? And indeed, don't we all experience this tension on an intimate level?

First, about the tension I speak of, I feel all my mathematical poems produce tension that can be interpreted in many ways. You speak of the specific (the mathematical) versus the general (the words), which seems valid to me, although my words are often specific, too. In my discussion of "Mathemaku No. 10" I give the opposition producing tension as mathematical answer-seeking versus verbal question-revealing, which is more exact, I feel. The long division contraption in that work is one invented to lead to exact answers, but I feed very fuzzy "numbers" into it, including the drawn heart, all of which seem calculated to sabotage calculation and any kind of exact answer. Over-all, I feel that the following oppositions are in effect, besides the general versus the specific, and answer-seeking versus question-revealing: vagueness versus exactitude, the connotative versus the denotative, complexity versus simplicity, art versus science, sentiment versus hard-headedness, the person versus the impersonal, intellectual slackness versus intellectual rigor, intuition versus reason, the concrete versus the abstract, and probably others. Most of these are pretty similar, but I think the concrete versus the abstract is important, and significantly unlike the others.

When I speak of "getting a person into two (or more) places in his brain at once," I mean it literally, for I believe that the brain is divided into what Howard Gardner calls "intelligences" but I call "awarenesses," and dive further, into "sub-awarenesses." In the case of my poem, the aesthcipient who experiences as I want everyone who comes into contact with it to, will "read" it in both his verbal sub-awareness and his mathematical sub-awareness. He may even weakly read it in his visual sub-awareness because of the heart.

I suppose there are many ways of interpreting the tension that will probably arise, but mine has to do, simply, with what the aesthcipient expects of the poem and what it actually does against those expectations, or—more exactly in terms of my theory of psychology—what his brain, relying on past experience, predicts that the poem will lead to, and what it actually leads to. The tension results from the expectations or predictions going wrong, and the brain's attempts to adjust. What happens, I believe, is the brain lays down a pattern for the poem to follow, based on previous poems the subject has been exposed to, and sends out warning signals when the poem fails to follow the pattern, and tries to find a logic that will render the poem nonetheless harmless. Part of the derailment here consists of the poem's going into arithmetic instead of properly remaining words—or, more likely, going into poetry instead of remaining a proper long division example.

In any case, we call the signals symptoms of tension. Or, as I believe you have it, signals of the need of some kind of resolution. I suppose one can call the whole process intuitive, but I consider it neurophysiological and thus entirely rational. But, then again, I consider intuition a form of rationality. It differs from "normal" rationality only in that it carries out its function before the subject's verbal awareness has begun describing to the subject what it is doing in "thoughts." The resolution I believe the person involved automatically seeks can be anything that allows the poem, finally, to make sense—usually some kind of enlargement of the initial pattern called into play, or its revision, or even its rejection for some other pattern. Properly to discuss this would require several thousand words about my theory of psychology that I'd prefer not to have to try to come up with right here. Suffice it to say that the resolution here is the aesthcipient's realization that the poem's words are both verbal symbols and, figuratively, numbers, and the heart a graphic symbol and number, and that the idea that the heart times "poetry" will yield "somewhere, minutely, a widening" is logical, makes sense, can fill a pattern synthesized from the patterns for "heart-felt poetry will enrich a life" and a times b equals c—to put it very roughly.

The resolution should produce a satisfaction; meanwhile, the brain's gyrations in trying to find a resolution will cause it to try many patterns out, relaxing the memory into a looseness which throws it into a wide range of the connotations the words and heart can lead to. The hope is that some of these connotations will be sensual—for instance, in this case, that the aesthcipient may actually experience a door opening very slightly on a sunrise or something. This would put him in one extra place, and also fulfill another major aim of poetry, for me, the conversion of words back to what they stand for, or the sensualization of the reading process. In your terms, I would say the poem causes a flawed intuition which does battle with the poem that, if successful for the person involved, leads to a final idea—more an image complex, in most cases—that corrects the intuition and resolves the problem.

I like your idea of the poem's having a "tension-quotient, and this in proportion to the problem—or, 'the thrill of solving' that problem—that it poses." That my mathematical poems have the potential to give someone the thrill of solving them is, in my view, a salient virtue of them—or, really, of any poem. I hope they have many other virtues.

As for what we can take literally and figuratively in this poem: All the words are to be taken literally, and the heart as a smear of its recognized symbolic meanings: "heart" and "love." And also as your "synecdoche for the whole of one's desires." The literal meanings of these things should include as many of their reasonable connotations as possible. The long division apparatus is to be taken literally insofar as I intend a genuine long division to occur, but the long division it tells us about is a metaphor, the words and heart metaphorically doing various kinds of arithmetic.

The "aesthcipient" you ask about is merely a person experiencing an artwork. It is a poor coinage of mine because of the difficulty of pronouncing it. "Auditor," which it replaces, is superior in all respects except for its connotation of judgmentality. Lately, I've leaned toward the latter term, anyway. Some word, however, is needed to indicate a reader who must do substantially more than read to appreciate an artwork or a viewer who must also read and perhaps do other things to do that, and so forth. It has nothing to do with "intertextuality," I don't believe. I'm not sure, though, because I don't know what that is, though I've come across the term enough times. I'm not a reader of Kristeva.

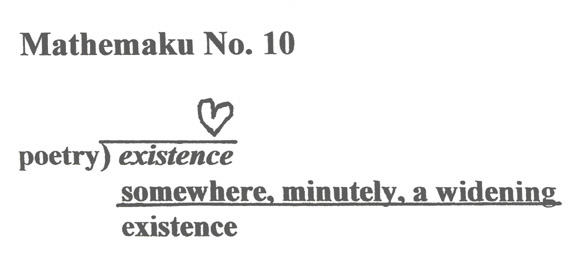

You speak about poetry as not totally an intellectual experience, a sentiment with which I completely agree, although I would claim that it is never not an intellectual experience. As for my relationship with my poetry, I consider "Mathemaku No. 10" a statement of that relationship. In it I say that sufficiently inspired poetry will produce a minute "widening" (in one's experience) that is almost equal to existence at its height (italicized). In other words, poetry is powerful stuff (and I intend it to be a synecdoche for all the arts). In fact, the poem shows that mere "existence" (unitalicized) is substantially less than what poetry can produce, or: existence is nothing without poetry. An irony about this poem is that it is so much an assertion that I almost think of it as advocature rather than literature—propaganda rather than art. Only the possible sensuality of the heart and the phrase, "somewhere, minutely, a widening," deflect it (I hope) into what I call art. My "Mathemaku No. 6a" and the two other poems in the set it begins seem to me much more personal.

I'd like to stay with the consideration of "tension" for a little longer because I think it has relevance to poetry generally—and that is to both the poet, in his artistry, and to the reader, in his artistry (as it is by way of recognizing that the reader, in his encounter with the poem, must bring to the reading a certain proficiency, a certain artistic proficiency or sensibility or imagination, that you have, I believe, put forth your idea of the aesthcipient, for as you point out, some term is needed to indicate a reader who must do substantially more than read). Now I find the term aesthcipient (which I suppose does force a sort of lisp but which I've always pronounced est-ipient, for better or worse)—which is I believe one of your earliest coinages, and which I think says a whole lot more than "auditor" which has its root (interestingly, especially for sound patterns) in to hear and which does, somewhat inappropriately, I suppose, carry a sense of judgmentality (although aesthetic judgments are just that, judgments)—can be used two ways, that is to mean the reader generally, and then to characterize that reader who has been educated so as to perform his role (or, do substantially more than just read) in the realization, the making, of the poetry (for by no means is this a passive role!). In light of this I'd like to interject a quote from Roy Harvey Pearce, from his book The Continuity of American Poetry, published in 1961: "This text presents such difficulties—especially with its peculiarities of punctuation—that some critics have insisted that a 'regularized' text is needed. Yet I wonder. For Emily Dickinson's punctuation forces upon her reader the demand that he punctuate—i.e., modulate so as to achieve form and meaning—as he reads. Thus she makes the reader participate directly in making the poems and calls into play such powers of imagination as he has." (This is the clearest, most succinct statement of the matter that I've ever seen—and indeed, one can write an entire doctoral dissertation on the idea expressed in this statement!) So: I think when you speak of expectations going wrong and the brain's attempts to adjust, you are speaking, if I may, to the first sense of aesthcipient, that is to the reader generally. I see your goal—if you'll excuse my forwardness—as being to educate the general reader into the ways—the methods and resources—of the aesthcipient. Or such is where my interpretation is leading me.You cite a number of "oppositions" that you feel are in effect in the mathemaku (and by "in effect" I take it you mean are present there, are in operation there, are either actually or virtually in force), but it seems to me all these other oppositions can be treated separately from what I would consider to be the primary "opposition," and that is the tension between the general and the specific; but I would not term this tension an "opposition," I would not say the general and the specific are in opposition, and I would not state the case as the general "versus" the specific. I think when we state a proposition in terms of one thing "versus" another, we are basically creating an either/or alternative, an alternative whereby 1) the resolution (and perhaps we ought to bracket that word) may take the form of an intermediate idea, but one according to which both identities are transformed, are compromised, or 2) the [resolution] is such that the one is transformed or subsumed into the other, with one taking precedence over the other. Rather, I can conceive of these oppositions as standing on their own, in the form of an opposition, and having significance as such. The tension that, let us say, accompanies this significance is then [resolved], or more accurately, addressed, not by neutralizing that opposition, but by sublimating this tension into literature—and I'm thinking in terms of my artistry as a poet, and of my artistry as a reader. (I think this fits your idea of the aesthcipient.) Such works of literature, and of art, are then, I think, truly cultural products (and have significance beyond their identification with a school or movement—nay, such identification can obscure the poetry, forcing attention, rather ironically, on the writer's intentions, affiliations, etc., instead).

We're still left with the tension between the general and the specific. This is, I think, the primary problem for the poet; but more accurately, this is, I think, the condition, the state of affairs that the poet accepts; and we may judge of the poet's proficiency in this matter by the degree to which his words—his diction, his choice of words—manifest this tension (and in light of this, I would say that where modern poetry, in particular in Eliot and Stevens and Cummings, shows symptoms of becoming problematical, postmodern poetry is problematical; this is the condition, the essence, if you will, of postmodern poetry). I think this is done superbly in the mathemaku; and by way of defending this assertion I would begin by pointing to your diction, to your choice of words.

In the mathemaku form you have created, you are not writing sentences, whereas a sentence would consist of, for instance, a subject, a predicate, a main clause and subordinate clause. Yet what you have to work with is the dividend (subject), divisors (predicates), quotient (main clause), and each stage in the division (a subordinate clause). You are not writing "sentences"; yet, still you are expressing thoughts—in words! And so each word you choose has quite a burden, quite a load to carry, quite a role to play, because it is only one word, one word that must do the work of several words; or a handful of words that must accomplish the work of a complete sentence. And when a word will not answer your purpose or requirements, an image, such as your hand-drawn heart, must be decided upon. The work of how many words does that hand-drawn heart accomplish! That is an instance of poetry. That is but one instance of how you, the poet, suffer the manifestation of the tension between the general and the specific!

But no one has imposed this form on you. Why mathematics? Why mathematical symbols? A poet is supposed to use language! Now in your poetics, in your literary investigations, you seem so at home in the language, and in pretty good command of it; you've coined many neologisms, you've given new senses to words, you've written eloquently and insightfully on a good number of difficult topics. . . . What happened, what sort of breakthrough or development or turning point or crisis precipitated this turn to math in, of all your writing, what is your most intimate mode of expression?

First I have some quibbles about what you say about my term, "aesthcipient." You say you take it to mean "that reader who has been educated so as to perform his role. . . ." For me the term does not mean the "reader" but the "recipient" of an aesthetic experience, such as a person listening to a concerto. So, yes, "substantially more than just read"—but also "not necessarily read, at all." I would also quibble with your calling an aesthcipient one who has been educated so as to perform his role. That may be so, but there are also aesthcipients who have "learned" to perform their role. (Note: I'm motivated here by my bias against formal education.) I would point out as well that I use the term, "aesthcipient," more neutrally than you seem to want to: for me, an aesthcipient is simply a recipient of an aesthetic experience. Whether he is a perceptive one or not is beside the point. Later you say something about an aesthcipient's expectations going (as I would put it) wrong / right, asking if that goes along with my definition. Yes, but only when the aesthcipient has a successful aesthetic experience. He needn't have one, however, to be an aesthcipient.

Now going over what I said before, I've come up with a replacement for "aesthcipient": aesthespient. Aes-THES-pie-ent.

About Emily Dickinson. As you know I'm not a big fan. I still believe that she punctuates as though she were a punctuational illiterate—and I think due to a dislike of hard work. In any case, she uses dashes everywhere. How that forces a reader to punctuate, as Pearce claims, I don't know. It forces me to try as best I can to ignore her incessant breathlessness. To force a reader to punctuate would require a writer to leave out punctuation, I would think, not put in inept punctuation. I think it a duty of a writer to use clear language and punctuation. I don't go in for reader participation in anything but where the writer's connotations go. I do think that a poet should maximize the connotative potential of his work—but not by mystifying its denotative value.

I'm not sure I wholly follow your discussion of oppositions real and apparent. An example of a poem in which a generality and a specific interact would be helpful. I go along with both "(1) the resolution .. . . may take the form of an intermediate idea, but one according to which both identities are transformed, are compromised," and "(2) the [resolution] is such that the one is transformed or subsumed into the other." But I think both occur. I would add that one needn't take precedence (as you claim): the ideal would be each reaching peak strength simultaneously. To put it in concrete terms, at least according to my theory of psychology, I think the general term turns on a different area of the brain than the specific term, and that the successful poem gives the aesthcipient (or aesthespient!) a way to connect the two turned on areas.

When you say, "Rather, I can conceive of these oppositions as standing on their own, in the form of an opposition, and having significance as such. The tension that, let us say, accompanies this significance is then [resolved], or more accurately, addressed, not by neutralizing that opposition, but by sublimating this tension into literature—and I'm thinking in terms of my artistry as a poet, and of my artistry as a reader," we may well be using very different language to say the same thing. All I can say for sure is that I don't think in terms of sublimation. I think in the strictly concrete terms of two images that cause the equivalent of static in the brain because they don't connect—at once. Once the aesthespient connects them, if he does, he experiences pleasure (by, sure, expressing his own artistry.) That's it. The tension is his discomfort due to the static. Yes, I guess you could say that in getting rid of that tension by connecting the images, or whatever, he sublimates it. I prefer to think he cures himself of it. Probably because I don't go along with much of Freud's concept of sublimation.

I'm not sure what you're saying when you speak of artworks "as truly cultural products" that "have significance beyond their identification with a school or movement" that "can obscure the poetry, forcing attention, rather ironically, on the writer's intentions instead." It's hard for me to understand how an artwork can have any significance through its identification with a school, or how a human being can make anything that is not a cultural product.

My next quibble is with your use of the terms "modern" and "postmodern." I don't like them. They are attached to chronology, which is not very relevant—because some "modern" poetry is as "problematic," for instance, as any "postmodern" poetry, and much "postmodern" poetry is less problematic than much "modern" poetry. I prefer my term, "burstnorm," to describe all poetry that breaks convention, starting with Pound and Eliot, and continuing through the so-called Language poets, and pluraesthetic poets. Another key trait of many artists called postmodern, by the way, is their willingness to combine expressive modalities, often in a not very problematic way, except for aesthespients who can't accommodate mixtures of the arts, or of the arts and sciences. I don't much care for the term "problematic" as a critical term, either. What is problematic, what not, seems to me an almost completely subjective matter.

Your discussion of my mathematical poems in terms of sentence structure is interesting. I'm not sure I entirely agree with what you say, though. The dividend would seem to be a long-division mathemaku's subject. The verb is the box it is in, which I call the "dividend shed," and it and the quotient and divisor make up the predicate. Actually, I would consider a long division poem to contain more than one sentence. A second sentence would consist of the divisor and quotient, and their product. A third would consist of the product, the remainder and the quotient. Yes, "subordinate clauses," as you have it, I guess. (I would love to know the established term for what I call a "division shed," but have not been able to find out what it is, or even if one exists.) It is true that I generally compress my poems as much as possible, as you seem to be saying. The best haiku are my models for this. But I have also used complete sentences, and whole paragraphs, and even a complete page of a book, in my mathemaku. Anyway, what you're so flatteringly saying my texts do seems to me what the texts of any poems are intended to do. I can live with your focus on the general and specific in my mathematical poems, but I really don't feel I think that much in those terms when composing them. I think more in terms of the abstract versus the concrete. Not that that is much different from the general versus the specific.

I'm

not sure my most intimate poems are my mathematical ones, for I believe

I've been quite intimate in many of my other kinds of poems. Deciding

how intimate a given poem is, is a rather subjective matter, anyway.

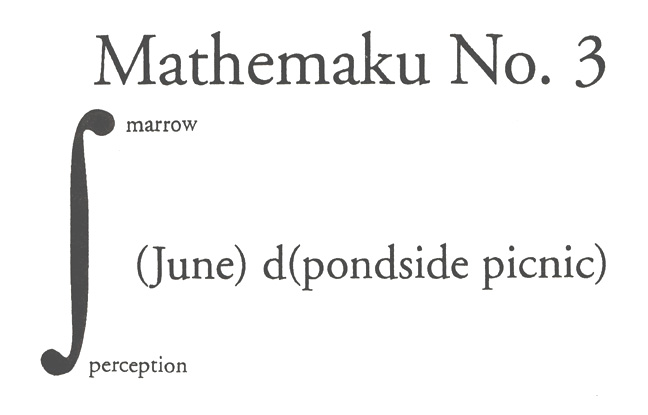

As for the origin of my mathematical poems, I think I started making

them simply because I've always wanted to find new ways of saying things.

I saw the potential of mathematical symbols almost immediately upon

seeing the symbol for integration used with words instead of numbers

in a piece by Louis Zukofsky. I had the same experience with regard

to typographical experiments when I first saw what Cummings did with

them. A simple Wow, look what you can do with typography, or math!

That was enough to make me do what I've done in burstnorm poetry.

Well I am taking liberties with my extension of your terminology, and I readily acknowledge that I'm capable of making a wrong turn, but I think you know this is the result of a sincere endeavor to appreciate your work. So let me try again: The point I wanted to make, ultimately—though I am also trying to relate ideas, not only in support of my point, but that I hope will spark some conversation—is that if we take the idea of the aesthcipient (or of the aesthespient, that is if you haven't modified the meaning of the word but have only changed a unit of distinctive speech sound), if we take the idea of the aesthcipient one step further, if we develop it and say of that development here we have a recipient who is also an inter-acter, one who is capable of reciprocal action, then we can expect of this aesthcipient the ability to appreciate the poems of Emily Dickinson, which (I do agree and I think it a totally defensible position) require that he read so as to achieve form and meaning, a form and meaning that will likely escape the casual reader. Indeed it's likely the casual reader will be baffled or even feel heckled by her capitalizations and dashes. (But just as an aside, all the same I would never suggest he reads from the early editions of her work, where the text was changed to conform to accepted usage. Dickinson, we now understand, was so fastidious, so meticulous about the deposition of her poetry—this whole other dimension of her poetry was suppressed.) And certainly this applies to the experience of music; a casual listener will enjoy a cencerto simply because it pleases him, and if you ask him why it pleases him, he'll say he doesn't know, only that it pleases him. (And certainly, that's valid.) But to the student of music (and one need not have a formal education to be a student of music—a sincere commitment will suffice), who understands for example counterpoint and who knows how to listen to it, I think his experience of the concerto will be something more profound than the other. There are composers, such as Berio and Cage, whose music (although in the case of Cage, it's the performer's music too, no?), I think, defies casual listening; you can't tap your foot to it, you can't keep time with it; rather you must familiarize yourself with it, learn and understand its rules, train your ear to it; it is an acquired taste; and the aesthcipient who has acquired a taste for this music is experiencing this music at a level that is simply unavailable to the casual listener, or such is my extension of your terminology.

Would you say your aesthcipient—who is simply a recipient of an aesthetic experience (and I take that as the formal definition of the term)—is equal to what I mean by casual reader / casual listener? (I sort of think so, especially when you say, whether he is a perceptive one or not is beside the pioint.) What then determines whether the aesthcipient has a successful aesthetic experience? Does it depend on the poem, or in this case the work of visual poetry? Can it be said that ultimately it depends on both the piece and the aesthcipient? And about my casual reader, one last thing that might help make my point: Yes, even a casual reader is capable of trains of associative thoughts and feelings, but I don't want those thoughts and feelings to be automatic!

I

don't have anything more to say about Emily. As for my term, and I'll

go with "aesthespient" now, though it's losing its initial

appeal for me. (A recipient of an aesthetic experience IS my formal

definition of the term.) It is not equal to what you mean by casual

reader / casual listener. It is equal to ANY reader / listener

/ viewer / smeller / perceiver / feeler / etcetera-er, casual and uncasual.

As to what determines whether an aesthespient has a successful experience

of a poem, first I would distinguish what he experiences aesthetically

from what he gets from the poem in other ways—e.g., the thrill

of reading An Important Poem, say; the thrill of having known its author;

nostalgia—maybe it was a poem his Mother adored; its political

content, which he rilly buhleeves in; etc.

What he gets from the poem as an aesthespient is mainly dependent on

what is there on the page, and his ability as an aesthespient to see

the counter-point, as you have it, AND his ability as a human being

to go into the reasonable connotations that are there. For instance,

in my "Mathemaku No. 10," the line "somewhere, minutely,

a widening" should take a willing aesthespient almost anywhere

any poem, or analogous culturework, has ever brought him—to the

specific feeling of life's getting momentarily much larger—although

also only fractionally larger—as explicitly forced by the text—and

also to forced thoughts / feelings about other data whose specifics

will depend on what the aesthespient has brought to the poem—such

as, in my case, Basho's crow / autumn image, or Shakespeare's "tale

told by an idiot," or the elation I felt when I first understood

how RNA works, etc. The kind of data is implicitly forced, but

the details subjective.

It occurs to me that the term aesthespient is perhaps likely to be misconstrued to mean something like recipient of Greek tragedy, or, recipient of acting, in that "-thes-" might be taken for the root, that is in that it might bring to mind the word Thespian.

Perhaps the confusion is with my use of the term "postmodern," which for me has more to do with metaphysics (which you deny the validity of—you refer to yourself as a "scientific materialist") than with aesthetics, or chronology, as you would have it. For me the term postmodern refers, not to the reciprocation expected of the reader (his participation in the production of meaning, or, otherwise, what detail his subjectivity will bring to the data "implicitly forced" by the text), and not to the integration of otherwise disparate media, and I am least of all concerned with it as a matter of chronology, but to the problem of signification (a problem by way of inheritance and imposition). And so this is a problem, really an affliction, that has stricken the poet, whose calling it is to make words mean something. And I speak here of the poet as entirely separate from the reader. In my economy there is a science of the poet, and that science is the science of meaning—the metaphysics of signification. When I speak of the problematical, I am pointing to the problem of signification; signification, which has become fraught with uncertainties. The sense of doubt, and the possibility, nay the intrusion, of nihilism, which is the absence, the eclipse of meaning. I do not question the possibility of nihilism, the actuality of which occurs in equal pace with the eclipse of signification. Or, like a sponge-eraser it can absorb and obliterate signification and leave in its wake a black hole. The postmodern poet, his condition, his situation, is to be faced with that black hole, or else to know the pull of its gravitational field. The first casualty, in the poetry, has been the metaphor. And think of what metaphors do: metaphors produce semantic changes, and thereby increase language—new concepts are formed, and concepts give way to new classes and categories, new insights and new paths for action. This sort of increase in language is obviously of a different nature than that which comes of the concocting of neologisms. Today, in our world, the metaphor has been replaced by the neologism. And we are fools to think the neologism can increase our minds, our language, conceptually, the way the metaphor has. The whole possibility of the metaphor has become problematical.

And so I see in the mathemaku the working-out of this problematic (whether in whole or in part), for instance in how so few words—as in the haiku—must carry the burden of so much meaning, and for instance in how your narrative line has been so compartmentalized. While on the one hand, your narrative is linear and we must follow it in the steps of the division, on the other we are immediatey faced with this compartmentalization (I dare not say, compartmentalism); we see it, it is completed, and yet to know it we must walk it. How do you conceive of your narrative line? Do you think at all in terms of narrative? Is narrative a problem for you, or do you consider it in terms other than to be a problem?

Two things have always struck me about your mathemaku and about your poetics: The first I can sum up in one word: lyrical. I find in your diction a spontaneity, a whimsicality and, yes, an unabashed sentimentality, and that is what I mean by lyrical. The second thing (and this is primarily to do with your poetics) is that you seem to be constructing a Ur-poetics, that is to say you seem to be going toward an original or proto poetics, and this as distinct from building on what others have said and done before you. Am I correct in this impression? Or else, whose work do you see youself as building upon? What other poetics systems do you admire and, well, appropriate from?

You and I seem near-obsessive about defining our terms so it's hard for me not to respond to the first part of your "question" with ten- or twenty-thousand words. But I fear I'd get confused, anyway. Make that "too confused." So I'll just say that I tend to agree with you about "aesthespient," but it's my best attempt, so I'll stick with it for now. As for your ideas about nihilism, etc., I will only say that I believe in certainties and the ability of words to express them. If I didn't, I wouldn't waste my effort trying to explain myself here. What would I use to do so?

I'm quite ready to say more than a little in response to your interesting packet of remarks and questions about narrative, compartmentalization, lyricism and poetics, though. The first of these, narrative, is not something I think about much when composing my long division mathemaku (and long division mathemaku are about the only kind I currently compose). I guess, though, that you could say that each of these is the story of one image's division into another, and must be followed linearly. But I also feel that in one sense I liberate my images from ordinary grammar, so producing a collage effect, not—I think—compartmentalization. On the other hand, by making each image a separate term of a long division example (e.g., divisor or remainder), I compartmentalize them more than the author of a conventional poem compartmentalizes his images.

I hope, too, that the poems make interesting designs, though the verbal is always more important to me than the visual, so sometimes my mathemaku are plain, or even ugly. I'm speaking of my last two or three dozen. The first ten or fifteen were only very occasionally visual—though even with them, I tried for pleasant-looking "stanzas," appropriate to their subject, like most poets always have.

Narrative does come into play overtly in my mathemaku sequences, which generally show some kind of evolution—for instance, in my "Mathemaku for Beethoven" in which a dividend in its "dividend shed" attracts divisor, quotient, etc., and in four or five steps becomes a finished, or solved, long division example. But plot is rare in my mathemaku, which are mostly situations only: images thrown together and forced to interact in a surrealistically mathematical way to see what will happen.

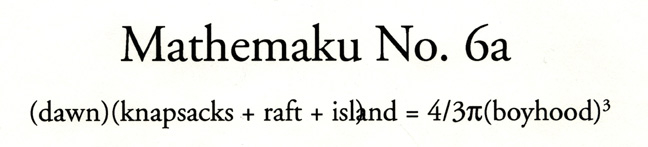

There is a bit of narrative in another set of my mathemaku, "Mathemaku into the Spectrum," or whatever name I've given it, or will give it. I just finished the fourth in this series, "Mathemaku into Violet." The other three are on display at (Thank You) Eratio. In each of these there is a lengthened long division narrative, but I also try for a vague narrative along the top of the dividend shed—most effectively, I think, in "Mathemaku into Blue: "winter sleep thought Proserpina timelessness"—with the last word truncated to indicate the unfinishedness of the narrative (and the poem as a whole). I won't say what story I read from this, but I hope a similar one will be there for others, and / or other stories. I also hope the rest of the poem contributes to whatever story the top line tells.

As I was writing the above, I thought how little different what I've described is from what I earlier described (if I remember rightly) as a scattering of images on a page for an aesthespient to make whatever he can of, but I do believe there's a more strongly implied narrative in these top lines I've been discussing than there would be in a genuine scattering.

I'm pleased that you and others find my work "lyrical," even though I suppose everyone has a different idea of what lyricism is. For me it has to do with a focus on a single image or interelated image-cluster. It is divorced, for me, from songfulness, though I'm all for aesthetically effective sound effects—or auditory images—in a poem, even a visual poem. I do tend to go along with Yeats and so many others in hoping my poems come across as spontaneous, however infrequently they truly are. After thinking about it just now, though, I wonder if spontaneity ought to be as prized as it is; it would seem that not being spontaneous is now considered a serious flaw. I don't think I've ever tried in a poem to seem unspontaneous, but it strikes me now that it would be quite valid poetically, and a nice change, for a poem to seem very thought out, very worked on. I'm sure some poets have tried for that, but I can't think of any, right now.

As I've admitted before somewhere in this interview (I believe), much of my work is sentimental (as you describe it), or—as I guess I'd prefer to call it—celebratory. Often whimsical, too (as you also suggest)—but never, if I can help it, only whimsical. I hope most of my poems make people smile. Of course, I also hope to produce higher enjoyments, enjoyments that last. Lyricism, for me, means joy unalloyed with morality or any kind of "teachings." (Not that I don't veer on occasion from pure lyricism.)

And now we get to your questions about my poetics. One reason I was unprompt in doing my part in this portion of the interview is the size and complexity of that topic. It's hard for me to deal with any aspect of it in brief. Even to say much about my poetics' main sources, I feel I have to work out just what it is, in reasonable—therefore lengthy—detail. Actually, I'm not sure I have a poetics. I guess I do. At first, I thought that if I had any poetics, it consisted of little more than the hit & miss comments I've made in reviews that indicate a general outlook on the nature of poetry. Certainly, I have a taxonomy of poetry, but that seems to me a basis for a poetics rather than a poetics, or part of a poetics. I also have, if only in uncirculated manuscripts, a substantial theory of aesthetics, but I've rarely applied it to poetry. Perhaps, I will here.

Is whatever I have a Ur-poetics, or a Ur-anything? I suppose my taxonomy is a going back to a proto-taxonomy. But only slightly. It is only a development of a fairly wide-spread definition of poetry as lineated prose. One of my teachers in the early eighties used that as her working definition. I'm sure I've seen it advanced in critical writings from long before that, too. In any case, it was my definition 25 years or so ago. Whether I took it from someone else or arrived at it without direct help, who knows. It is so empirically sound, I should think many people invented it independently. Where I've been at all original is in extending it to cover texts without lineation but offshoots of it that I consider poems—and for application to forms like visual poems that have no real lines to lineate. I bring in the concept of what I call the "flow-break." A flow-break is simply some sort of blockage in a text where words would be expected if the text were prose: a large white space at the end of a line that would continue to the edge of the page if it were prose for instance, as in standard lineation. Or such a space in the middle of a line, or at its beginning. It can also consist of asterisks, or any other kind of symbol (or spoken sound) without a clear punctuational or other semantic use. Poetry, in my taxonomy, is verbal expression that makes consistent, significant use of flow-breaks. (All writing has flow-breaks, but in prose, they're sporadic, incidental, rarely significant.)

My rationale for the centrality of the flow-break in my definition of poetry is that, for me, poetry's main function is to use words to put people significantly into the sensual sections of their brains. Prose puts them into the verbal sections of the brains, and rarely does anything to put them into their sensual centers (although, in narrative prose, a text tries to put readers in what I call their sagaceptual sections—and, usually, in the anthroceptual, or people-related, sections, of their brains, as does narrative poetry). The aim of the flow-break is twofold: (1) to signal to the aesthespient that he is in a poem and should open his senses, and (2) to slow down the aesthespient so the words and other matter he takes in have time to awaken sensual images and feelings. Of course, poetry uses other means to accomplish these things, such as the use of richly sensual images, a beat of some sort, or the sound or visual appearance of words. A poem's emotional effect is important, too—but not in determining whether it is a poem or not, only in determining the value of it. To get back to what I was saying about lyricism, I try entirely to give pleasure with my poems, so consider them successful to the degree that they cause that emotion. All these aspects of my poetics are pretty standard, though I—like just about all critics—have my own idiosyncratic way of talking about them. I'm not up to outlining my whole poetics—and I now believe I have one. I do think it built on what others have done in the field, starting with Coleridge and heavily including the new critics—and excluding your favorites from France! I. A. Richards, T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound are among those I most admire among prior critics.

It does occur to me that I ought to mention the central place of the

metaphor in my poetics. For a while, I considered it a defining

element of "true visual poems": I felt that a visual

poem had to combine its visual and verbal elements into a consequential

metaphor to be taken seriously. I've since lowered my standards—since

no one else will accept them, but also because I have to admit that

few verbo-visual texts meet my standards, even among my own, and that

many combinations of the verbal and visual manage to do a great deal

without metaphors, or the equivalent. I think at one time I even

believed that textual poems required metaphors. Williams's "The

Red Wheelbarrow" changed my mind. I still hold that—"equaphors,"

as I term all verbal expressions in which one image is directly or indirectly

equated with another—are the most important of the poetic devices.

They are the best means of putting people in "manywhere-at-once,"

which I claim in my book of that title is what all the best poetry tries

for. In that book, I mention other means, including rhyme (which

puts an aesthespient of a poem in the auditory part of his brain while

the verbal meaning of the rhymes keeps him in the verbal part).

They can sometimes be extremely effective, too, so I would never belittle

them. But equaphors—principally metaphors—seem to

me to have the potential, at their best, to do much more than other

poetic devices.

You mentioned that you started using color in your mathemaku work. In your book, Doing Long Division in Color (2001), are these the first pieces you did in color? The three pieces we have here—"Mathemaku into Blue," "Mathemaku into Red" and "Mathemaku into Yellow"—were not included in that book, and I imagine "Mathemaku into Violet" is part of this new, or separate, series called "Mathemaku into the Spectrum." First, can you tell us something about your use of color—for instance, what is the significance of the color, and of the use of color as such, what role does it play, is this your way of playing to another area of the brain? Also, you have kept the mathemaku form and now you seem to be expanding on its possibilities (for instance, a further dimension, a chromatic dimension, has opened via the addition of color, and what's more the works now seem more the result of assemblage or collage), would you say that you have entered into a transitional phase in your mathemaku work (you seem to be exploring the mathemaku both as a means to an end—a means to a poem—and as a device as such—for the pleasure in the pursuit, one might say)?

Is there anything else you'd like to tell us, by way of introduction or annotation, about these three from "Mathemaku into the Spectrum" (you have already mentioned their narrative)?

I've always been interested in working with color but the cost of reproducing

colored works kept me from trying anything much with it, even when I

was playing around at being a comicbook composer in the seventies.

(I've never been that interested in making one-only artworks—I

think like a poet, I guess, wanting to make my art distributable.)

By the late nineties, the revolution in computer and printer technology

had made color feasible. One could now "print" colored

works on cyber-air for almost nothing that would be available to anyone

with a computer. Even making pretty decent hard copies has become

substantially cheaper. Hence, when several friends of mine in

the field started sending me copies of work in color a few years ago,

I decided to try my own.

At that time mathematical poems were about the only poems I was making.

They still are, as a matter of fact. So I began thinking

of how to use color in one of my mathemaku. These, incidentally,

had not originally been graphic in any way. I only gradually made

them visual, including a visual touch or two in a few until "Mathemaku

for Ron Johnson," which included, as its dividend, a complete visual

poem appropriated (with his permission) from a sequence Johnson did

(and, I later learned, John Furneval graphically tweaked). It

wasn't until my "Odysseus Suite" that I made a mathemaku that

was as visual as it was verbal and mathematical. Three of the

four poems in that sequence contain elaborate compositions using overprinting

and a previous minor poem of mine about light that used highly customized

typography. It was only with this sequence that I began thinking

of my mathemaku as designs, with their verbal content becoming almost

secondary. That was where I was when I decided to try color.

The step to that wasn't much of one, but I was timid. Hence, I

chose just one color, a primary one, for my very first poem in color,

which was "Mathemaku into Blue."

As I was making this poem, the obvious occurred to me: making

a poem for each color in the whole spectrum, or for at least the three

primary colors. So I jotted down ideas for red and yellow equivalents

as I was working on "Mathemaku into Blue." When I finished

it—sometime in 1999 or 2000, I think—I had fairly extensive

sketches done of the yellow and red ones, but never had the time to

make final versions of them. I was still using cut and paste (with

real scissors and glue) at this time, not having or knowing how to use

any paint software.

My next venture into color was "Mathemaku for Beethoven."

A sequence, it was less timid than "Mathemaku into Blue"

so far as the use of color was concerned, for this time I used not only

standard blue, but an off-shade of it! A little later I did another

sequence that used color, "Mathemaku for Mike Basinski."

Here, I finally used a full palette, helped by the fact that I was trying

for something almost entirely unplanned, in keeping with what I took

to be Mike's way of composition.

I did no more colored mathemaku, and few poems of any kind, until I

got invited to participate in a two-week workshop at the Atlantic Center

for the Arts (ACA) in New Smyrna Beach, Florida, by Richard Kostelantz,

long-time Important Friend and Colleague. He had won a gig there

as "master-artist" with the privilege of gathering eight to

twelve under-artists to work with him, all expenses paid. This was a

huge break for me because Richard also invited Kathy Ernst, John M.

Bennett and Scott Helmes as well as some younger artists to work with

us. The atmosphere, sharing of ideas, and just being with people

turning out sizzling work, was terrifically beneficial. But the

best part of the experience for me was being introduced to Photo Shop,

a computer program that allows one to do all kinds of graphic things

on the computer. With almost full-time tutoring from the always-patient

Kathy, and help from Scott and others, I got semi-functional with the

program, and was able to complete around ten new full-color works using

it. Two of these were "Mathemaku into Red" and "Mathemaku

into Yellow."

Soon after my ACA experience, I hand-made my limited-edition of Doing

Long Division in Color—but I wasn't fully satisfied with

"Mathemaku into Red" or "Mathemaku into Yellow,"

so didn't want to include them in the collection, as originally planned.

I kept the blue one out, too, thinking I would eventually do

another limited edition that would be devoted to my "spectrum"

mathemaku only, and that it would be appropriate to hold "Mathemaku

into Blue" out for that.

Since then, I've done almost nothing but mathemaku in color, although

it was many months before I did a new one. Just recently, during

another two-week vacation, though, I made five new ones, and got five

others close to finished. One of the completed ones was "Mathemaku

into Violet." I am determined to do a mathemaku into orange

and one into green, as well, but only have a few ideas so far for them.

Since each of these poems are the equivalent of five or more

of my normal mathemaku, they take a lot of ideas! My ultimate

hope is to have ten poems in the sequence, adding ones "into"

brown, black, white and grey.

As for what I think I'm doing with color, it varies. In my spectrum

mathemaku, I'm trying to poetically analyze single colors. In

"Mathemaku for Beethoven" I also used a color, blue, as a

kind of object, dividing it into the sky. In my poems since then,

however, I've used color as a visual artist more than as a sort of scientist.

That is, I simply use colors that look good to me—provided,

of course, that they also seem emotionally appropriate where I put them.

I hadn't thought about it before, but I guess my use of color

does play to another significant area of the brain, for I'm sure there

is a sub-area of the brain devoted to color alone which my colored pieces

activate, thus giving the aesthespient another "where" to

inhabit at the same time he's inhabiting his verbal, mathematical and

shape areas. (Note: while I think IQ tests are trivial and not

especially revealing, it is curious that in the only at all extensive

one I ever took, my scores in verbal reasoning, mathematical reasoning

and spatial relations were all within a point or two of each other.

I refuse to state those scores except to say they were considered

high, but not exceptionally high, so I'm rather ashamed of them.)

I do feel like color is letting me into a significantly new world.

I've always wanted to make pictures and by using color in my mathemaku

I get to do this as safely as one can—because I feel the words

and form will automatically carry the works I produce regardless of

how amateurish the graphics. I do not feel like I'm merely dabbling,

though, but finding all kinds of visual things to explore, quite consciously.

Bob Grumman in situ: