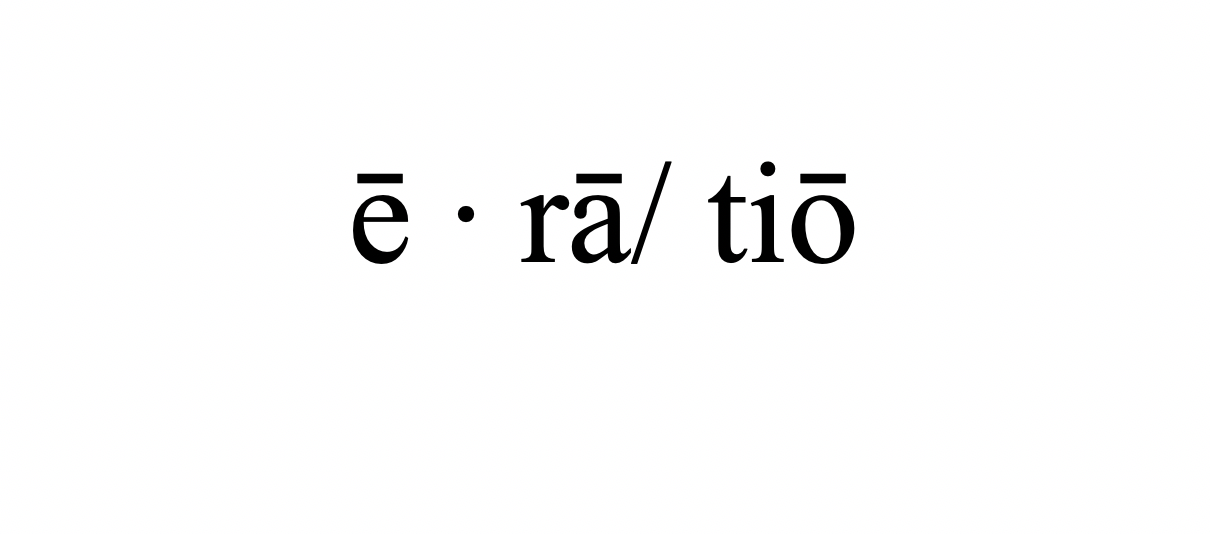

RETROSPECTING:

An Interview with Artist Roberta Aylward

by Contributing Editor Coleman Stevenson

Roberta Aylward’s creative practice is driven by curiosity and experimentation. With a focus on process and materials, her abstract work documents unseen memories, feelings and emotional landscapes. She received her BFA from The College of Santa Fe in 1991. Her work has been included in exhibitions at the Tacoma Art Museum, Oregon College of Art and Craft, Marghitta Feldman Gallery, The Gretchen Schuette Art Gallery, and Umpqua Valley Arts Association. She practices art-making daily in her Pacific Northwest studio, creating paintings, drawings, sculpture and collage.

Aylward and I met initially on social media through a shared interest, as artists, in tarot. In fact, we both often think about creative practice in terms of the tarot. For example, Aylward is very playful and process-oriented when she paints, moving through the establishment of a new piece without any set plan, a very Fool-like way of operating. The 3 of Pentacles card serves as a way to think through personal work vs. work that is revealed to the public and the creative support that arises from making those connections. When we finally met in person a few years into following each other, the “3” cards in various suits had been coming up for her a lot — she pulled one before our meeting — which started an ongoing conversation about creative practice, some of which is captured here. The following interview was conducted through email exchanges and during a visit to her studio in early November 2021. To see her main body of works in series, visit RobertaAylward.com.

CS: How does the Pacific Northwest environment as opposed to that of the Southwest impact what/how you create?

RA: These two geographic locations are so far apart in my timeline I feel less able to speak to the differences between them in terms of their impact on what/how I create. I cannot deny being impacted by my geography, but the environment of my home, family, friends, peers, collaborators and social media have all affected my behavior more so than geography.

.jpg)

A shelf in the studio displaying inspirational objects.

As I have grown as a person and an artist my work has been most impacted by relationships. For example, a collaboration earlier this year with local designer Tiffany Kirkpatrick of Parker Simonne Designs changed my creative trajectory when she reached out to ask if I’d be interested in painting a collection of fabrics for her designs. I am attracted to Tiffany’s work and admire her inspiring use of collage in her wearable art and happily agreed. Collaborating was a powerful reminder of what we can create when we work in tandem, what I can learn from seeing another artist’s process firsthand and an invitation to experience vulnerability through creating something together.

CS: This feels like a natural fit since you often treat your canvases like fabric in the way that you hang them.

RA: Yes! With the series Taking Shape I started pinning the canvas to the wall instead of stretching it.

CS: Why was that?

RA: I like keeping things open, experimenting as I go. If I stretched it on a frame, it created a boundary I didn’t want. I didn’t want to be hemmed in.

, 64x92 inches, acrylic on canvas with grommets, photo from the artist.jpeg)

Moon and Venus (2020) 64” x 92” acrylic on canvas with grommets, photo courtesy the artist.

, 43x62 inches, acrylic on canvas and muslin with grommets, photo from the artist.jpeg)

Visible Woman (2020) 43” x 62” acrylic on canvas and muslin with grommets, photo courtesy the artist.

CS: I was struck by these quotes, from your website I believe, that say so much about your process as an artist: “My creative practice is led by curiosity, rooted in experimentation and enlivened by play.” “I create for the love of the process. I don’t approach creating with a predetermined subject matter or meaning. Rather, ‘meaning’ emerges through the process itself: choosing a medium and materials; assigning color; creating shapes and lines that are in tune with my memories and sensations; and arranging the myriad elements to make them work in concert.” In a recent interview with Robyn Love, you also stated that you have a “devotion to the mark-making.” Why do you think your focus came to be more heavily weighted to the process side? What can be achieved for you in a flow state that cannot be found with precise planning?

RA: My process of doing anything is a balance between the two sides of my brain: the analytical and the intuitive. Through my art, and writing about my art, I can see that I pay more attention to the side that wants to play. Now, I can’t altogether play without being a bit responsible to the measurements, details, materials, functionality or salability of my work. What I do is try to keep my thoughts out of my work — mostly “shoulds” about my work — once I get started. So, there is a threshold I cross from thinking to non-thinking in the studio.

I want to jump right in to see what happens, switch to a spontaneity setting, enlist trial-and-error practices, let go of what I think. Devotion to mark-making is about letting the medium have its way and not trying to push my agenda. Unexpected things emerge when I hold the brush lightly.

What can be achieved for me in a flow state? Pleasure. So the sooner I can get there, the better.

CS: When you’re creating a painting, is there a point at which your editorial self takes over from your intuitive self in order to finish the piece? Is this different in your collage work?

RA: With larger and more involved paintings I take more process photos and this can lead to edits. I may explore what a piece looks like upside down or in black and white on the screen and then make changes to orientation or value. Often, viewing a large piece on a small screen will bring to my attention some aspect that can lead to change. And, sometimes to finish a piece I may decide to sign it so that I may not work on it any longer.

For example in this piece [Aylward gestures to a large canvas, a painting in progress, on the wall], the most recent one I’ve made, I knew at one point I needed to tone it down by greying the colors. In the end, it’s not a short story, it’s not a poem, you’re not using words, so I want to direct the viewer on some path, which can happen with adjustments like this. . . .

A painting in progress in the studio.

Smaller pieces, most collage or paintings created in a day, are more spontaneous and are finished before I start to think more consciously about changing them. With those pieces, I have the freedom to move things around until I achieve the sense of balance I’m looking for. I like the balance of organic and geometric forms, of structure and fluidity. I’m building something.

[I want to note here that Aylward’s collages are deceptively simple. Before composition occurs, she has already done a lot of work treating/texturing the papers that will be used to construct the collage. Papers are painted, stained, distressed, cut, and torn in preparation, so her collage process is much more layered than just layering the shapes themselves.]

7x10 inches, acrylic, watercolor, ink on paper.png)

Levitation (2020) 7” x 10” acrylic, watercolor, ink on paper.

Looking Glass (2020) 7” x 10” acrylic, watercolor, ink on paper.

CS: I’m always thinking across genres for these articles and want to note that this issue is something that poets, in particular, deal with frequently in their work — that balancing of states required to finish a poem. This makes me also want to ask if you are ever thinking in words as you create or if it’s always entirely beyond the logic and direction of language.

RA: This is a great question. Yes, I do have an ebbing and flowing dialogue happening in my mind as I create and words do emerge. I wouldn’t say I’m in some kind of trance state when I create. I definitely weave in and out of thinking and feeling modes.

I also write as a part of my practice to process thoughts, feelings and emotions — art-making being my more outward form of expression. Sometimes a particular word or phrase will stay with me and end up in my drawings or paintings. I have a series of works that began with words that are then fully or partially covered by the painting, indistinguishable in the end.

Text as image.

CS: This makes me think of that great Frank O’Hara poem, “Why I Am Not a Painter,” in which the chiasmus occurs as he discusses visiting the studio of painter Mike Goldberg who’s working on a new painting. There’s this crossing of genres and the idea that where one starts is often not where one ends up.

RA: I love the poem!

CS: Why do you choose to obscure the words/phrases that sometimes appear in your work?

RA: If you can read it, that’s all it’s about. Words are a very direct way to say what I want to say, but I like word games . . . not saying too much but saying something. I’m very fond of the way text looks, too — the architecture of it.

Sometimes words are just starting-off points, a way for me to ask How do I feel, what am I thinking. But I can’t have that in my painting — it’s a real sentiment, so I turned it into something like bridge scaffolding. They show an underlying structure that is no longer useful, so obscuring them is creating a new structure in its place. The initial text is an idea but it’s an old idea, sort of like moss on a rock it’s growing into a new idea that is a more satisfying expression. But often when some time passes it ends up becoming the title of the piece anyway. [Aylward laughs.] Art making is very therapeutic.

.jpeg)

You See Me (2016).

CS: What about the pieces you’ve made that use letter-like forms but do not actually contain words? Those are almost like sigils. . . .

RA: These pieces have forms that look like text and appear to assert. The process is a bit like rewiring the brain: destroying and creating; eroding and rebuilding. The original drawing is obscured, giving way to a second, bolder, abstract message.

Sigil-like forms.

CS: Given your interest in process, are your finished pieces supposed to mean or be? What would you say to people who worry about not being able to understand the meaning in abstract art?

RA: I would say both. Sharing my art has become a vital part of my creative process. Each piece is a different expression of what it feels like for me to be human. My art will undoubtedly mean different things to myself and others and while I’m fascinated by what my viewers think and feel — what their own experience is in relation to my art — I don’t wish to impose my own meanings on my audience beyond adding a title.

It is my wish that my finished works be something that inspires curiosity or emotion or contemplation or conversation or connection in others. I do wish for people to see my art, share it, and to live and work alongside it in their lives. My own experience with finding meaning in abstract art is that it is personal, it takes time and it is vital to view art in person.

CS: I think about how titles have been used in Abstract Expressionist works in particular, either erasing the need to look for a story by giving the piece a mechanical title or encouraging narrative by supplying the seed of a story (Franz Kline’s Painting Number 2 and Mark Rothko’s No. 61 (Rust and Blue) vs. Norman Lewis’s Every Atom Glows: Electrons in Luminous Vibration and Helen Frankenthaler’s Spaced Out Orbit). You seem drawn to narrative-provoking titles (i.e., Sea Change, Visible Woman, Princess and the Pea). How important is the title for you in completing a piece? Do you have a title in mind at some point during the creation or only afterwards when you assess what you have made?

RA: Agreed! I am fond of narrative titles for my work. I like to marry a piece with a title both for myself and my audience. A title can be the beginning of a conversation with the viewer like a hello, a hand-shake or a “nice to meet you” without holding a viewer’s hand or leading them by the nose. I am fond of word games, word play and etymology. Finding a word or a few words to describe my take on a piece is a kind of closure and usually happens near to the end or when a piece is finished. Sometimes a piece surprises me and names itself.

[Aylward also noted in conversation that open-ended titles are the perfect balance of this for her — something to steer the viewer, to bring them into the work, but not control their thinking too much. For example, the title of her 2019 series, “Stone Woman,” helps the viewer begin to piece together the stacked shapes before them, and titles of individual works in the series (“Jump for Joy,” “Embrace”) provide a seed of a story, but it’s still a story the viewer has to tell.]

55x47 inches, acrylic on stretched canvas, photo from the artist.jpg)

Jump for Joy (2019) 55” x 47” acrylic on stretched canvas, photo courtesy the artist.

46.5x37 inches.png)

Embrace (2019) 46.5” x 37” photo courtesy the artist.

CS: In that same interview with Love you state that “the movements I make to make the pieces are becoming increasingly important to me.” Speaking of the Abstract Expressionists, I’m thinking of Pollock “dancing” along a canvas on the floor, finding rhythm for his painting in his body’s motions. Can you tell me more about your take on this?

RA: I think what is increasingly important to me is disengaging my mind when I create and for this movement is key. I may move my paintings from the wall to the floor and back, turning them upside down and sideways. I like to paint with both hands, together and separately, too. Larger movements are less likely to be controlled and can have surprising results. I often begin with gestural line drawing to give me some structure.

CS: How does the mystical factor into your work?

RA: The mystical factors into my art as it factors into my life. I have moments of feeling a sense of awe and amazement and endeavor to capture them in a tangible form. I paint from dreams, memory and sensation — all unseen. Making art is showing up for a relationship with something I can’t quite understand and having to trust that there is more to it than what meets the eye. When things click or surprise me in a painting, or line up just perfectly in a collage, I embrace these moments and take any synchronicities to mean I’m on the right path, which I think is a mystical approach.

[As this interview is being conducted, we are on the verge of a Venus Retrograde that occurs every eighteen months and lasts around six weeks. Venus is the planet associated with beauty (art), love, and commitment; some believe that such a retrograde influences us to reassess those parts of our lives. This one is taking place in the Zodiac sign of Capricorn, and the last time it occurred in that sign was December of 2013, eight years ago. This astrological timeline provides an intentional framework for what Aylward describes in the following part of the interview. Aylward has aptly termed her process “retrospecting.”]

Retrospecting in progress.

CS: You’ve previously stated a preference for “starting anew each session” rather than working back into an existing piece across multiple sessions, however you’ve recently had an impulse to reexamine work from the last eight years using the current planetary energy as motivation. Tell me a little about your “retrospecting” process and why you think it is currently calling to you. Might you go so far as to directly alter the original pieces as part of the exploration, or is this more of a conceptual discovery?

RA: I am currently looking back and re-viewing, re-examining and most importantly re-valuing my drawings, paintings and collage from the past 8 years — which happens to be the length of time I’ve been in my current studio. In 2014 my son was four and I had newfound energy and time to create in a brand-new space. It was the beginning of a period during which I produced four solo exhibits.

This urge to revalue my work has forced me to slow down and take stock of what I’ve made; a process of organizing, documenting, and cataloging drawings, collage and paintings. This body of work comprises mostly sketches and studies for finished pieces over the last 8 years. Some of it is cataloging it and putting it to bed, but I’m also mining the past. Through this I am finding a lot of beauty that I had skipped over in haste as I created the next thing. I am finding meaningful threads through the work that I hadn’t noticed before and feel myself moving away from “starting anew each session” as I enter the studio. I feel this is the beginning of a new commitment to my work and myself and hope that I may discover some of my previous studies, and themes that emerge, are the seeds for new work.

I hope to learn patience, how to slow down my creative practice to be more deliberate with what I want to say. I see that there are patterns and threads throughout my last eight years of work; what I want is to be more intentional without losing all my spontaneity. Usually, I paint in one direction without stopping to look back. The idea for the show comes at the end. I want to be more focused on one thing. I want to set an intention before I work.

I greatly appreciate Aylward’s alchemical process of integrating of her different bodies of work and her obsession with finding balance, with working through an idea / exhausting a concept through series. I’ll close this interview with perhaps the greatest signature an artist can have — handmade tools. Aylward and I talked a lot about breaking free from convention, especially how often we as artists are erroneously told that certain tools are the “right ones” or only ones for the job if we want to be “professional” artists. Perhaps my favorite items in her studio were these pine brushes she makes. They are rough yet elegant, exactly the sort of balance of opposites that drives Aylward in her work.

Aylward’s handmade pine needle brushes.

Roberta Aylward is online at RobertaAylward.com.

Coleman Stevenson is a contributing editor at ē· rā/ tiō.

7x10 inches, acrylic, watercolor, ink on paper.png)