ANYTHING CAN HAPPEN

a conversation with artist Noelle Barce about creative practice and her Fugue Series

introduction and interview by Coleman Stevenson

Noelle Barce

Noelle Suzanne Barce is a Portland-based visual artist who has been making art under the moniker Epochal Void for the past ten years. According to Barce, “the name Epochal Void comes from a dream. It is a relationship between time and space that does not identify with a particular gender, race, or socioeconomic class, and thus, may move freely, always in flux, constantly becoming.” Her work spans many genres — conceptual drawing, painting, fine art printmaking, mixed media art, paper sculpture, lettering, and collage. Barce has indicated that her overall body of work explores concepts of impermanence, betweenness, and social & spiritual bondage. She describes her process of making art as “a gesture of freedom, of liberation from the constraint of measurement, definition and expectation.” Beginning in the fall of 2016, Barce has provided a variety of other artists space to explore their personal freedoms with her Trust Art Collective, an independent, artist-run organization that produces group exhibitions and creative gatherings.

She works both large and small. The works in this Fugue Series are all 6” x 8”, but other recent works have stretched as large as 96” x 48”, presenting the viewer with unknowable landscapes of color splashes and dimensional texture. Encountering one of these pieces is a bit like standing on the edge of a cliff. You fear you might fall in and you also want to jump. Somehow, there is the same greatness of spirit contained or expressed in the smallest works as in the largest. The vastness feels maybe even more present when it seems to be pressing against the sides of a confined space, desperate to break out, as in the pieces that comprise this series.

Tell us a little about the Fugue Series, its creation and themes.

Fugue is a series of conceptual drawings that explore the issue of constantly changing identities in the modern world. Rather, the ways in which our identities change in order to adapt to the consistent demands of the world. These pieces are dynamic, tangled, expressionistic — of my own feelings of anxiety about having to flip back and forth between modes of being. Acting and communicating one way, with certain people, in a certain environment — work, for example — and then immediately having to present myself in another way, in another place — home, the grocery store, social gatherings, art events. . . . The goal being survival, of course. That subtle, underlying threat of social failure, that when I really think about it, seems silly to worry about, but it’s there.

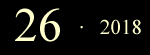

Fugue 1

What materials have you engaged for the Fugue Series and how do they inform your composition?

The media consists of acrylic ink, aquarelle (watercolor) pencil, and graphite. These three mediums are all capable of transcending their original forms, from completely opaque and solid, to sheer and light in coverage and texture. I’ve always been taken with drawing because of its narrative capabilities, and its provisionality. Drawings are known for being preparatory — as figure studies for painting, or blueprints for architecture, or storyboards for theater. I like open-endings, rhetorical questions — this is why I like art. The idea is to encourage, and perhaps celebrate the question. In the case of a drawing, one wonders is it finished? Am I?

Your recent work has a fascinating juxtaposition of features and forms. The pieces in the Fugue Series and other works have a geometric quality, but also an explosive freedom about them. What does this combination of opposites mean to you?

Each black-and-white drawing suggests a tension between opposites, in this case, the impulse to grow and change, versus the fixed, flatness of the plane on which it exists. Balance and structure (order) are achieved by adding sharp lines and geometric shapes. This also suggests the “grid,” the invisible network of electric lines that connect us with the rest of the world, but also isolates us. The combination of binary elements on the same plane achieve, for me, a more accurate representation of life with all its diversity and chaos.

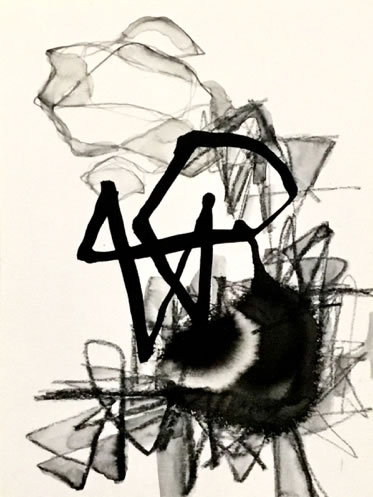

Fugue 2

Can you tell me about the role chance plays in your creative process?

In the past it was easier to know when a piece was finished because it would look like how I imagined it. Everything was measured, lines were drawn, demarcating spaces, giving shape and dimension to forms. The meaning was contained in what was being portrayed, a setting, a figure, a plant or animal. With this work, meaning is communicated through gesture, material, color, space. A huge component of my work these days involves restraint, even submission. Instead of having to be in control of each mark, I let gravity create the form by tilting the surface and letting the ink run where it will, creating a more organic mark.

As a poet, this is all very interesting to me. It feels similar to the struggle to find meaningful external form for a poem. Sometimes there’s freedom to be found in imposing a fixed form, a rigid structure on a poem. Then you get to play with more organic rhythms on top of that.

When I started studying art seriously, the first thing I learned was that it’s easier to be creative within a structure, than without. In my experience, if a project is assigned to a class, and the expectations with regard to theme and objective are wide open, then no one really learns anything, do they? Gotta know the rules to break ’em.

Fugue 3

Fugue 4

Your work ranges so widely in terms of size. How do you know when a piece needs to be large rather than small?

Perhaps my work grows larger when my voice needs to be louder. I made the series Controlled Bleed during the 2016 election, the media’s coverage of the police killings of black men, and the Women’s March (which I was unable to attend). The largest in that series is a diptych, with two 3’ x 4’ (36” x 48”) wood panels, meant to be hung vertically, 1” apart, called Doublespeak. Fugue is part of the same series, and they were shown together. In a way, Fugue is a series of actions, and Doublespeak is a more singular statement. Possibly about multiplicity and confusion. (And sometimes, it’s just the materials I have on hand!) (Doublespeak is named for the song by Nico Muhly on Filament.)

Your early work as a printmaker and illustrator is extremely representational and detailed. That couldn’t be more different than your current style. Do you think these two eras of your work speak to each other in any way?

I think I am trying to communicate the same things, but through abstraction I can speak directly to the viewer’s center (Heart? Soul?), bypassing that part of the brain that “reads” images by making associations with existing forms, languages. When one communicates through narrative, all of the responsibility for the creation of meaning falls upon the artist. Perhaps it is an attempt to even the playing field, to encourage the viewer to use their imagination, or to respond authentically to what they are experiencing. I’ve been trying to resist didacticism ever since I realized that might be what I was presenting through illustration. Hours and hours, days and days of drawing plants, animals, people — this teaches you how to focus, how to look and take into account the details that give life to renderings. It is possible to develop this skill until you are able to draw from life, from memory, with ease and a higher rate of success — success being measured by one’s ability to communicate clearly one’s intentions. I still work like a printmaker, in layers. But I am not the type to work on one piece for days and days. I work in series, adding a single layer or color to multiple panels, then assess, and add the next layer. So I make a lot of art, most of which will never be shown, but never be thrown away. This is important. I feel, in a sense, like a collector — of color, texture, pattern, all provisional materials for future compositions.

Makes sense, too, that if you are abstracting you must already know well the exactness of the thing that is to be abstracted. I am a firm believer in learning rules well before breaking them in writing as well. Dismissing the use of fixed form without understanding its value makes for weaker free verse poetry, or often poetry that is all narrative and no music.

Right! That goes back to what I’ve said about how much figure drawing informs my current practice. That’s why many — dare I say, most — prolific abstract artists have some measure of skill when it comes to traditional drawing.

In a recent artist talk, you discussed how changes in your physical abilities changed the aesthetic and, ultimately, thematic content of your work. Could you tell me more about that?

There are some people who must constantly create in order to feel happy and fulfilled. When I’m not in the middle of multiple projects, I feel idle. A few years ago I was studying printmaking at Portland State University, managing a gallery, and doing regular exhibitions. Because of my penchant for procrastination, I found myself preparing and printing an entire edition of etchings for a final project. Additionally, the gallery I was managing was striking an installation that required painting the gallery walls from black back to white. I spent a couple of hours painting baseboards, then went to my studio to prime some panels for a mural project, and rode my bike home. The next morning (which happened to be my birthday) I woke up paralyzed by pain from back spasms.

This was the great turning point for me. I experienced a series of overuse injuries to my back, wrists and hands, and could not draw, write, or sit for extended periods. The irony of knowing that because of my dedication and enthusiasm for my craft, I was no longer able to participate in it, was unbearable. So I was faced with a choice, like we so often are. It seemed that my only real option was to change my perspective on what I was doing, and ultimately change how I made art.

Often we get stuck in our own routines, making work the same way, with the same expectations. It is crucial to be open to change, because anything can happen. I’ve seen countless creatives give up on art because they had to move out of their studios, or no longer had access to materials, or never sold anything. The ability to adapt is crucial because the world is constantly changing around us. This may be why I still use the name Epochal Void — that sense of detachment has really helped me, conceptually, with that big change.

You mention procrastination. It seems there is a certain magic in that for many artists. Does it provide you with needed pressure to finish? Does it force you to be more spontaneous? Why procrastinate?

While it does add a layer of unnecessary pressure, it’s how I’ve worked for a long time. Perhaps this comes from a compulsion-toward (and exhaustion-from) process-intensive projects. Or perhaps having less time to prepare, keeps me from overthinking everything and doubting myself. I do try, sometimes, to plan way ahead, months ahead, a year. I always end up changing my tune a couple of weeks out, so I may as well do it when I feel it most.

Fugue 5

Fugue 6

Contributing Editor Coleman Stevenson has been a guest curator for various gallery spaces in the Portland, Oregon, area, and has also taught poetry, design theory, and cultural studies at a number of different institutions there. She created the Image + Text track in the Certificate Program at the Independent Publishing Resource Center where she has taught since 2015. Noelle Barce is online at instagram.com/epochalvoid/.