from the collection Earlier

Rosanna E. Licari

Liminality

The new virus takes control and first responders set up beds in tents and stadiums — makeshift hospitals swarming with medicos scrambling for PPE and even raincoats because that’s all they’ve got. The infections and deaths are broadcast daily. As we withdraw into lockdown, quarantine and social distancing, there is fluidity at the margins. A gateway for the wild. Animals edge into the vacant spaces. Shoals of fish swim through clean Venetian canals, emptied of speedboats and cruise ships. Ducks have laid eggs at a vaperetto stop. Sika deer wander into Nara’s streets and subways. Goats from the headland run through Llandudno and give hedges an extra prune. A puma from the Andes explores the curfewed streets of Santiago. My species paces the pavement on approved morning and afternoon walks. Isolation brings a consciousness that notices tree bark and the neighbour’s flower beds. We observe insects and pollinators we cannot name. Distinguish the greens of the natural world. Prams, skateboards and pedestrians spill over streets, ignoring the road rules and the moving cars. The vehicles slow down, stop. Pasted on the back of a traffic sign, a lost bird notice: a galah is missing. Davy is microchipped with no leg ring. Perhaps in the animal ether he felt the spaces open. Glimpsed the spirits of squawking Cuban parrots, saw flashes of marauding sulphur-crested cockatoos. Then finding his cage door wide open, boldly and quickly, stepped out.

Lockdown

Don’t cringe when I say I miss the smell of chlorine at the public pool. I’ve been schooled in the dark arts of cleaning. My parents thoroughly promoted the benefits of handwashing, bleach and methylated spirits. Their lives filled with the European post-War diseases — tuberculosis, dictatorship and hunger. My time has come in a strange way. I have distanced myself socially since a child, so this is natural. There is plenty to do that doesn’t include others. Starting small, I tackle one room at a time then hone in on the intricacies of dusting and cleaning. Feather dusters, Superwipes, and clean rags fill my arsenal with the big guns of domesticity: the vacuum cleaner, the bucket and the mop. But, there’s time for distractions. A quick look in a wardrobe or jewellery box. Try on a forgotten piece infused with family memories. The coral necklace my mother gave me. A gift my father brought her from a trip to Florence. My tour of duty expands to the outer reaches of the house — the garage and the damp hollow under the kitchen that accommodates the side of the hill. I know now how my father felt when, after he’d shower, he’d say Don’t touch me. I’m clean. Hidden enemies are everywhere. People on their socially distanced walks become potential carriers. Any surface is a battleground. Home is the only demilitarised zone.

Jenolan Man, 1866

John Lucas finds himself among shadows

a cool draught on his face,

the earth, damp beneath his woollen suit.

He turns slowly onto his side,

towards the dim glow of a tallow candle.

He is in a cave.

Is it a new one?

He reaches into his waistcoat

drawing out the chain of his pocket watch.

No ticking. The arms as motionless

as the limbs of a stillborn child.

But he feels it again, like the first time

in the cavernous darkness,

the vast, monumental space

that can produce fear or awe,

depending on the man.

For Lucas it was always the latter.

The knowledge of his insignificance

in the face of the Creator’s work.

He left his mark when he ventured

into the caverns, autographing

the calcite walls, taking over

a hundred samples of God’s labour.

Standing, he expects to see the speleothems

as those in his study: clear, white and pink.

The light reveals nothing but broken

limestone columns, jagged drapery

hammered down and taken. No splendour

only the remnants of spars broken

into pieces among the gouged flowstone.

And there are names, many names

attesting to who, when and why people had come.

Divulging loves, hates, and the liquid crystal pools

full of broken glass, paper and garbage.

A searing pain begins behind his brow,

constricting thought into a ball of fire.

Shutting his eyes, he cries out as tears

stream down his face. Then his eyes open.

He is on the floor of his office,

his secretary kneeling beside him.

The doctor, Sir?

No. Get me some paper. I must write.

Note: The Jenolan Caves are in the lands of the Burra Burra people, a clan group of the Gundugurra Nation. John Lucas, Member for Canterbury NSW, began his campaign to protect the Jenolan Caves in 1866.

Feasts

Wings beat in quarter time

and the crush of leaves punctuates arrival.

Its floral display already captured

by the hunger of bees,

the mock orange now has new visitors

that eye off its small ripe fruit.

Bodies of grey and copper fur and

bone tracking into flat, leathery planes.

Winged reputations smeared with virus.

The morning driveway is splattered

with seed-infused mush.

Reddish, sticking like glue.

These leftovers, hosed and swept

into the garden, will shoot.

Under the sensor light,

their nocturnal calls fascinate.

A flying fox swoops so close

we could almost touch.

Landscape

for N

They hide under sleeves, jeans and skirts. These cuts sculpt strange terrains in your flesh. I shuffle in the loose stones at the foothills. I know nothing of this topography. The experts say it brings relief. Fights the rock-hard numbness, frees those buried concerns. You’ve told me nothing. And now a flood of pills scour your throat and settle in a dark, acidic pool, dissolving another bout of apprehension. This is another level, an uncertain place. A lightless valley, cold and bare. Is there a map? The experts say it’s not always an endgame. I don’t know what to say.

Exiles

Mother tells me

when it’s all over

after nothing can be done

and both their bones mingle

in the grains of sand

and the decaying kelp of

Watsons Bay.

For three years

my aunt’s and uncle’s ashes lay

in the crematorium’s pastel-coloured boxes

for the right time

to have the ceremony,

for all of us to come together

in the same place, and

from that place

cast them into water.

There were no crosses.

No markers

to show they fled a war-torn land,

died in another.

I wonder why she agreed

to such a senseless request.

Once more, Mother insists

this is what they wanted.

They asked who would visit their graves?

Executor

Again, I say too much as this is my habit. If only silence came so easily. You return my call when I am in the middle of something. (A trivial thing.) Of course, I can’t help, but tell you. We’re friends after all. I dwell on you being alone in your dead brother’s house. It’s left to you to deal with “the estate”. Sometimes you think you see his shadow. In the living room you’ve hidden one of his religious medals in a gap between the wall and the door frame. You believe St Christopher will bring blessings to the new house owner. You’re giving away your brother’s clothes. The cat that you brought down from Brisbane wanders around the bric-a-brac and furniture that filled his world. The furniture polish left with the wooden chairs. The TV has sold and so has the sound system. A radio connects you with the outside world as your portable TV won’t work there. Now you’ve sold his car. Got the price you wanted. The microwave has also gone. Cooking dinner on the old stove, using one hotplate, has made you realise how little you need. You managed to make a meal of chicken and vegetables in one pan. Something in your voice echoes the reflection of a hermit. Once, by the seaside, you ate takeaway pizza in the fading light. Shadows dropped on your locked car. These always carry colour. Under the orange street light, mine is aqua green. I remember a blast of light from a shining sea. I imagine you lighting a fire in the middle of the backyard. Being content with the simplest of lives, unpopulated by people and things. You brother wasn’t like this. Everyone in town knew him. Bowls, cards, committees. His spirit is everywhere.

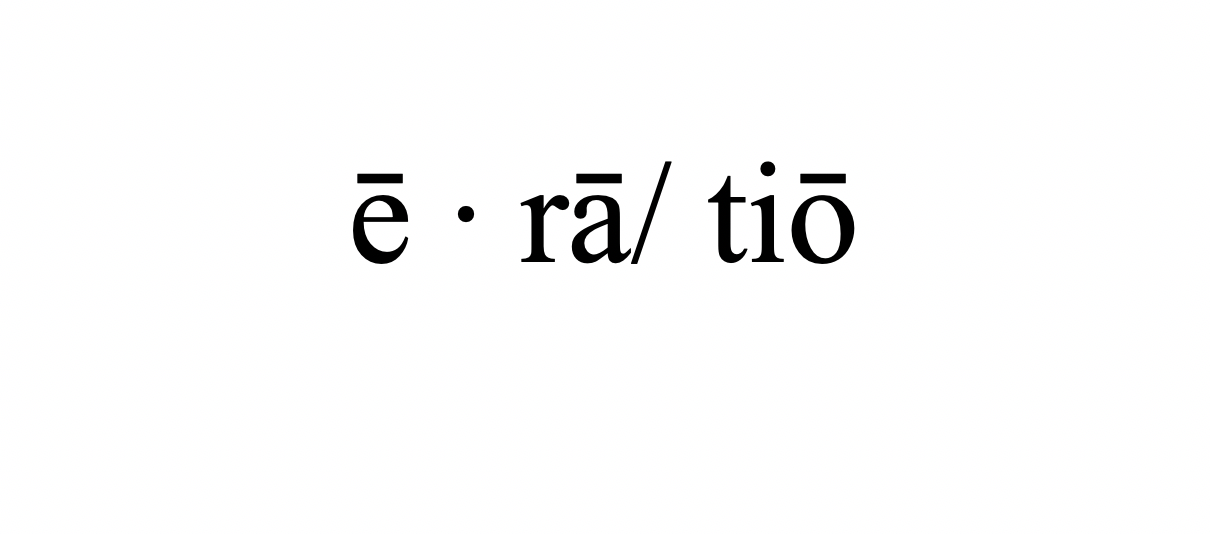

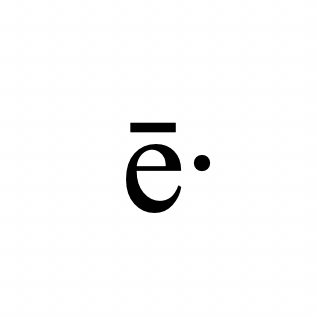

Rosanna E. Licari has an Istrian-Italian background and is based in Brisbane, Australia. Her work has appeared in various journals and anthologies including ArLiJo (USA), Australian Poetry Journal, e·ratio (USA), Meniscus, Not Very Quiet 2017-2021 anthology, Poetry for the Planet: An Anthology of Imagined Futures, Pulped Fiction: anthology of microlit (Spineless Wonders, 2021), Quadrant, Scars: anthology of microlit (Spineless Wonders, 2020), Shearsman (UK), TEXT Journal, The Anthology of Australian Prose Poetry (MUP, 2020), and Transnational Literature (UK). She received the 2021 poetry prize from the American Association of Australasian Literary Studies, and she is the poetry editor of StylusLit. She teaches English to migrants and refugees in Brisbane, Australia.