Alan Halsey

interviewed by Gregory Vincent St. Thomasino

2010

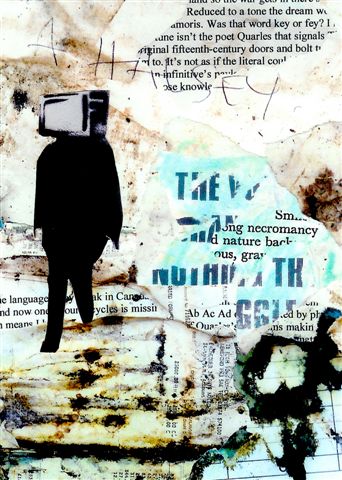

Is this a self-portrait? (The placement of the name, of the words, of the letters, “A. HALSEY”—this is something a reader cannot miss, is this something you want me to notice? And the title, “Memory Screen”—are these images (both the images of text and the images of things and of scenes) truly memoric?)

Text-graphic from the CD ROM slideshow, Memory Screen, included in the Five Seasons Press book, Marginalien (2005), and as a separate CD from West House Books. CD ROM production by Richard Urbanski at Nomad Media, playable on both Mac and PC. “Some pictures which without any warning preferred to be a book.”

Is it a matter of thinking-in-images—that is to say, do you have an idea first and then seek out an image that’ll best exemplify or extend that idea, or do you rummage among images to chance upon an appropriate, (a germane, a foil?) one? You seem to employ décollage technique as well as collage. Would you say something about your education in the (visual) arts (and about the history (the evolution, if you will) of your own perspectives and motivations, and about your own (quite various) techniques and procedures). . . .

‘Thinking in images’ comes nearest the mark, although insofar as the images (or rather their elements) are ‘found’ I can only usually work with ones I stumble upon by ‘chance’ (whatever that means)—consciously looking for them or rummaging hardly ever does the trick. I came across the stencilled figure with the TV head spraycanned on a postbox in Ghent. By that time I’d made around half of Memory Screen and wasn’t sure where it was going—and of course couldn’t have foreseen finding this image or for that matter any image which would act as such an effective counterpoint to the initial ‘Memory Screen’ graffito which I’d photographed in Sheffield. It’s all a matter of contextualisation, or rather creating a context in which a certain thing will work—I was making a text-graphic called Memory Screen and then I found this figure with a screen for a face!—at which point it becomes, yes, a self-portrait and that’s how I present it in the performance version. The background is worked from some old personal accounts papers which had got soaked and gone mouldy—collaged with some earlier settings of the Memory Screen text—and then my name superimposed from my accountant’s handwriting—so that it becomes an image of myself bifurcated between the workaday and taxable world and, what shall we call it, the imaginative realm where I dream I belong. The whole image then went through several versions and became the ground for the later pages of Memory Screen; among other things it allowed me to focus on the way a ‘screen’ can be something we see things on and/or (crucially) something which screens other things off.

To some extent Memory Screen stands apart from my other visual work, although it did grow out of the camera-based material and improvised text of Dante’s Barber Shop and I’ve been developing some of its procedures in a current sequence, In White Writing. But the sense in which the elements ‘present themselves’ to me and prompt me to find ways to re-present them is pretty much a constant. I know people generally see it as collage although in much of it there’s a good deal of drawing involved in both the first and final stages. Or, drawing as writing, or, writing as drawing. I love that expression of Klee’s, ‘taking a line for a walk’—that’s what I hope to do in both visual and verbal work and that’s where they connect. I’ve had no formal education whatever in the visual arts—my art teacher at school sent me packing from the class at the first opportunity. I was about fifteen then, and had been doing my own writing and drawing for a couple of years—the two things always came together, although writing seemed and still seems to be the main impetus—as if my visual work is a peculiar kind of writing. Perhaps I contradict myself there, or perhaps I just find it harder to see it the other way round. I have at times felt able to theorise about it—and of course I know there’s a body of speculation concerning visual/verbal relationships—but it seems largely pointless. There was a couple of years in the late 70s when I painted a lot of semi-abstract landscapes but apart from that I’ve found that I can only make visual pieces which either embody or respond to text or at least some textual element.

Do you perform all the technical procedures (the actual production, the manufacture, the assembly) by yourself? You are fluent in all the various machines and software? Do you take on interns?

I have to smile about the interns . . . even if there were any on offer they’d probably go insane trying to work with me. Apart from the collaborative collages such as Quaoar I’ve done with Ralph Hawkins I make the original visuals all by myself and sometimes do the printing too. But I’m no great shakes with machines and software, I just blunder along and see what happens. The Paradigm of the Tinctures originals were made by a technique I developed while working on Memory Screen, an overlay process not unlike traditional print-making methods such as lithography except that it’s all done on paper. The Paradigm colophon states that I used Photoshop but that was the printer’s simplification—there seemed no short quick way to describe my eccentric behaviour. I’ve only ever used Photoshop for transfer to the web. All the black-and-white work in Marginalien was made with pen and ink and scissors and glue and a stubborn old toner copier. These days I use inkjet which I like for its tactility. It interests me that you can do things with inkjets which can’t be done with toner copiers and that the reverse is also true. Perhaps it’s anomalous that although I’m not technically minded I do love playing around with machines and seeing whether they can be made to do what they’re not meant to.

As for book production I’ve been lucky to have had a thirty-year friendship and collaboration with Glenn Storhaug at Five Seasons Press. He’s published or produced all my best-made books and we’ve worked together for so long that there’s much we don’t need to discuss—we know by now how we each like things done—the joy and I hope success of our collaborations comes out of our friendship, can anyone ask for more than that? I’d like to say, though, and friendship apart: Glenn Storhaug has been the best book designer working in England for the past three decades and it’s long past time this was acknowledged.

I love Marginalien. I feel about Marginalien the way I feel about some records I own. It’s a totally welcoming and satisfying experience—and virtually inexhaustible, I know I’ll always discover or comprehend something new in these pages. When I listen to music my wont is to “listen closely,” and when I read poetry my wont is to enjoy a “close reading,” and what I appreciate, and admire, about this book is that this book rewards close reading. As for book production, Marginalien is quite simply state of the art, and, quite simply, epitomizes the small press commitment, a conscientiousness, to literature. Cheers to both of you!

Interns and the going insane. Reminds me of the Scorsese film, Life Lessons. But it’s a matter of instincts and intuition, and the exposure to these in their raw, authentic working form, and I do emphasize their raw, authentic working form, and in the form of a poet at the height of his powers. You can’t reproduce that in a classroom. To my way of thinking, you’re a resource. I hope they’re paying attention. . . . I understand what you mean when you say you’re not “technically minded.” I wouldn’t use “technically minded” to describe you, rather I’d say problem solver, and in this way your proficiency, your resourcefulness, and your ingenuity, which are all quite apparent. Remarkably so. . . .

I want to ask you about Paradigm of the Tinctures, your collaboration with Steve McCaffery, but while we’re on Marginalien: There is an intelligence about Marginalien, a sense of purpose, and I think this is apparent, first of all, in the layout, in the presentation of the material. The word that comes to mind is balance (a perfect balance of poetry and art) but I think maybe a better (more “Halsey”) word is reasonable distance. And I think here we have a key, a key not only to the plan or schematic, or, form of the book but to the subtleties of Halsey generally. Or such is my reading. . . . Reasonable Distance is the title of the third section of the book (and beginning page 39 we are still quite at the beginning, as we run to over four-hundred pages). We find the words “reasonable distance” occur three times in this section, at the beginning as the title of the section, in the middle as the title of a poem (“For Reasonable Distance”), and at the end in the title of the last poem in the section. This last poem is entitled “An Imitation, in a Prospect of Reasonable Distance, for K.C.” and ends with the line, “We’re setting off home along Broad Street / with the silk route behind us, I’m quoting from / memory a parallel text on the Altai Mountains.” These words, “I’m quoting from / memory a parallel text on the Altai Mountains,” but especially the words, “parallel text,” form, I think, the key to the vibe in this poem. The “Altai Mountains” are in Siberia, quite some “distance,” “reasonable” or no, away (and we’re quoting from memory, here, so this “distance” is both interior as well as exterior, as well as literal); the “parallel text” is a parallel situation; and the lesson (or, such is my reading) gained, and applied, is one of proportionality, one of insight and perspective. For me, this proportionality (or, “reasonable distance”) informs the aesthetic, not only of Marginalien, but of Halsey generally, and I think that is the key to your success. (Of course, “reasonable distance” can also be construed as, simply, good taste. . . .)

Reasonable Distance, reprinted entire in Marginalien, was a collection originally published as a pamphlet by Equipage in 1992. It includes practically everything I wrote from the end of ’88 to 1990—the last years of Thatcher, and some of the poems are heavily infused with the desperate politics of that time—Thatcher’s departure is of course the context of ‘Resignation Mimes’. I’m not sure how common a phrase ‘reasonable distance’ is but I had an in-law who used it frequently—she seemed deeply convinced there were a lot of people she needed to keep at a ‘reasonable distance’. It struck me as one of those phrases which expresses an evident meaning at the same time as it is fundamentally nonsensical—what can possibly be ‘reasonable’ about ‘distance’? This made it from my point of view doubly useful: it seemed to balance engagement and disengagement by teetering between the meaningful and nonsensical. And some of the poems in Reasonable Distance—‘Thos. Hood Quotes Coleridge and Continues’, for example—adopt the ploys of what is dubiously called ‘nonsense verse’. That last poem, ‘An Imitation’, celebrates my friendship with Kelvin Corcoran and in particular the long lunches we used to spend at a bar in Hay-on-Wye just along the road from my house and shop on Broad Street—no distance at all. But it relates also to two of Kelvin’s poems, ‘Music of the Altai Mountains’ and ‘Tocharian the I-E Enclave’ which begins ‘They say there is, along the silk route, / a life away, another language like ours, / used by people unlike us // Its way is lined with hoardings / across the figure mountains, real mountains / that will kill you if you stay out too long’. The Tocharian languages were spoken in the Tarim basin but belong to the Indo-European group, unexpectedly. So Kelvin’s poems provided ‘likeness’ and ‘unlikeness’ as well as the ‘distance’ and ‘parallel’, although I developed the latter terms with conscious ambiguity. I meant them also to reflect the way the poem is written in the present tense, as if the act of writing were simultaneous with the events recorded—of course not so at all, but it’s something poetry very often does, and as nothing else can—usually the poem is as it were ‘quoting from memory’ but the quoting is enacted in silence—I just thought I’d mention it for once. I wrote the poem in the middle of the night, straight through, with hardly a revision—‘in a Prospect of Reasonable Distance’.

Paradigm of the Tinctures is the title of your collaboration with Steve McCaffery. And here, you supplied the art and McCaffery the poetry. Coming upon this book my first impression is that of a cultural artifact, a time capsule, something the product of an archaeological dig. It’s the cover, and the color, this stark off-white, or, “bone,” or, it’s like something extraterrestrial, or like the color of the Space Shuttle. And nothing, except for the words “Paradigm of the Tinctures.” And it was unexpected, and I was happily surprised, astonished, really, to see that this book is constructed in the form of a continuous strip, but as though it could, or would, be a fold out! But as it is published it’s a page-turner, like an “ordinary” book. . . . Seeing this as a continuous strip, one immediately imagines the contents as panels, mural-sized panels on the wall of a museum. Have you ever had the opportunity to see these pieces blown up to mural size? I think my favorite piece is this one, entitled (or, accompanying the poem entitled), “THE POEM AS A THING TO SEE.” What is going on in this image, and how did you do this?

It’s one of the layered images I mentioned. One layer is a photo taken by chance—I was waiting to cross a road in Madrid and I had one of those single-use throwaway cameras which I was putting in my pocket—I accidentally pressed the button and it took a very useful picture of the pavement. Whereas the other layer is highly deliberated. I video’d a TV programme about Gutenberg and then took photos of the screen while it was playing back. I’ve taken a lot of photos like that—it’s a guarantee of the poor quality which is particularly handy for this sort of work—the elements need to be ‘distressed’ before they become manipulable. I was planning to make a text-graphic called Gutenberg: The Movie but it didn’t work out. I did write a text for it and that went into Marginalien. The images with many reworkings gradually diffused into other sequences and I used some in Paradigm, including ‘The Poem as a Thing to See’ (Steve’s title, as is Paradigm of the Tinctures itself). Gutenberg images seemed particularly apt for a collaboration between two ‘avant-gardists’ with a shared passion for antiquarian books and the history of printing.

I love the concertina format too. Granary has used it for other books and it’s wholly due to Steve Clay and the binder, Judith Ivry. When Paradigms was launched at the Cue gallery it was laid out in the continuous strip but the individual images were also projected on the wall while Steve (McCaffery) was reading the poems. In performance I’ve also projected Memory Screen on to walls or big screens, and that’s the nearest any of my work has come to ‘murals’. I’m a miniaturist through and through and I rarely make images larger than page-size in a standard book.

Your collage work, and as various as it is, is an exemplification of the crucial insight that the collage is not only a material production but is an intellectual-material production. I have some questions for you on poetics and such, and then on to the poetry, but, please, before we get to that: The Last Hunting of the Lizopard. This is, again, a collaboration, this time with David Annwn, whose poetry is here mated with your art. I’d like to quote a brief verse of David’s poetry, because it will, I think, preface and so help with what I have to say, and also because it is so excellent:

If Spyder or Aphyd myghte reade thise line, what ways

might hem devise: swarming kiton in matrices, appendices

lined with lacewings, words too tight for eye.

And this piece, of motto:

The Poet’s eye, in fine frenzy rolling,

Doth glance from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven;

And as imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen

Turns them to shapes, and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name.

Because I want to say I think the Lizopard is of such an “airy nothing,” as might some poet give a name and local habitation. . . . I thought on surrealism, and then symbolist, but the word I want to use to describe my impressions of this book is psychedelic (—psychedelic as in, “manifesting mind”). It is the language, it transports me, it alters my consciousness, and the place I’m taken to may just as well be the scenes (the senses!) you depict in your accompanying collage illustrations. That is what I see, what I see and what I read in this poetry and in these illustrations, a manifestation of mind. And I’m not so sure how much I want to give away, because I really want the reader to enjoy it for himself, to be entranced in his own way and as accords his own receptive intuition. I do want to say about this collage work, however, that while these are indeed collages, this is no way simply a matter of the “juxtaposed” image; no, I think rather it’s more they are, if you will, “constellated,” “constellated images,” as these parts come together here to form a totally new and other whole, and while remaining distinct! (Which is to say, they, the parts, are blended but not denatured!) About the Lizopard, who I have met on other occasions, all I’ll say is to wonder aloud if the Lizopard is not a sort of psychopomp. I’m sure enough to say it is something evoked; it’s conjured up; it’s a manifestation. The edition I am reading from is the signed edition limited to 150 copies (and is available from SPD, Small Press Distribution). I wonder is there another edition of this work, or is this up on the internet, or have you ever thought of publishing this on the internet?

The edition you have is the only one. I’m not sure how well it would reproduce electronically—to me it’s very much a work on paper, the text and the images have a precise placement on the physical page and it’s meant to be a page-turner—clicking ‘next’ with a mouse isn’t at all the same thing.

The book came about through a suggestion of David’s, that we collaborate on some kind of work using alchemical material. I’d kept some reproductions of alchemical engravings on my worktable for a while, thinking I might try collaging them one day. I hadn’t got far before I realised they were becoming another episode in the lizopard series and when I gave the finished set to David I told him the title was The Last Hunting—he then wrote the text without further prompting from me—I just revised a little and shaped it in its final form.

I came across the lizopard in a dream in 1999 or 2000, recorded in the first Hunting. Definitely ‘a manifestation of mind’. It developed from there through an email correspondence with Martin Corless-Smith—in fact it was Martin who identified the creature’s crossbreed nature and named it. Some of the later episodes draw on Robert Burton and Sir Thomas Browne and back through the medieval bestiaries to Pliny’s Natural History and Herodotus, with some use of Darwin, particularly The Voyage of the Beagle—becoming the manifestation of diverse minds—of the way we come to perceive animals, to regard them as emblematic and construct our sense of both their specific nature and their otherness. This was given a peculiar iconography in alchemical illustrations, although I’d say the lizopard itself is much more elusive than the alchemists’ salamander-dragons and suchlike. David brought an entirely new element to the series, crossing alchemy with the wilder reaches of genetic speculation and the nightmare visions of Wells’ Island of Dr Moreau (who curiously rhymes with Prospero)—realising a development I’d barely contemplated. There’s the thrill of collaboration.

Alan Halsey reading at Edge Hill University, February 2006. Photo by Peter Griffiths.

Is there anything in your poetry that signals (or that could or that should signal) to the reader that this is the poetry of a Brit and not of an American—or are circumstances nowadays such that any such distinction is so blurred as to be imperceptible, or, dare I say, inconsequential?

I found out when I lived in Wales that I’m ‘English’ rather than ‘British’. There’s some politics in that but the differences among the poetries written in the several countries of ‘Great Britain’ are clear to see. But that’s not to deny that various ‘avant-gardist’ endeavours cross those boundaries just as they cross the Atlantic.

My poetry draws on contemporary English vernacular often injected with specialised vocabularies and sometimes with older usage and conventions—in some respects I involve myself with ‘tradition’ more directly than a lot of poets dubbed ‘mainstream’. The specific historical perspective is bound to distinguish my work from anything an American would write. But at the same time I’m aware of some American response to my poetry which I don’t get in England, and this must reflect a perception which either overrides geographical or cultural difference or is enlivened by it. By the same token I feel an affinity with some American poets which I feel with only a few (but perhaps just as many) English.

Is there a distinction in the sensibilities—a lyricism, perhaps?

So that lyricism is somehow more available to an English poet? If so it comes with hazards, although a few contemporary English poets have mastered it. Michael Haslam, for example. I’ve enjoyed developing a kind of mock-lyricism, useful for satire.

Do British avant-garde poets take their cue (I almost said “marching orders”) from American academics? Are the Americans the tail wagging the British dog?

By ‘academics’ you mean critical theorists? I could certainly name some English poets whose work seems riddled with theory but it’s not true of any of those I’ve been closely associated with or have published at West House—Geraldine Monk, Kelvin Corcoran, Gavin Selerie, Martin Corless-Smith, David Annwn . . . I’d say they all write from a native base and have a natural bent towards finding new forms, new ways of saying, independent of any theory they may have read (but some certainly haven’t).

I’d quarrel with the suggestion that there has been an all-determining American influence here and point to some deeply radical English works of the 1970s—Prynne’s Brass, Crozier’s Printed Circuit, MacSweeney’s Odes, Forrest-Thomson’s On The Periphery, Griffiths’ Cycles—all written before the first issue of L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E. And Cobbing had been beating up signifiers for a couple of decades. There are certainly similarities and some cross-fertilisation in more recent work but one can’t ignore the differences. ‘Language poetry’ seems to have found a space to cross theory largely European in origin with a disruptive version of the Whitman-Williams quest for a poetic language grounded in American speech; an English poet has to be busier picking through local wreckage to find whatever’s worth either salvage or creative demolition.

A definite cultural difference is that American poets have been keener to see themselves as ‘interdisciplinarian’ and I suppose that’s partly why radical poetries have found a place in American academia. English poets have rarely sought that fusion and they wouldn’t find much accommodation if they did.

Is poetry the place for ideas—I mean philosophical ideas, philosophical concepts . . . and/or, is poetry in any sense in competition with philosophy . . . (ought it to be?) . . . or is it a question of does poetry have the apparatus, the grammatical form (the logical form?), in order to compete, in any way, with philosophy. . . ?

Bill Griffiths liked to insist that poetry can deal with any subject matter, and he set out to prove it. Plotinus, potatoes, prisons. Ideas as well as things!—& why not? But if you want to write philosophy you’re better off writing it in prose, if you want it to be considered as philosophy. Bill’s ‘A Review of Vegetables’ has some handy tips on cooking but that doesn’t make it a recipe book. The same would be true if its subject were philosophy. A poem’s autonomy overrides its subject, or should do; the corollary being that the anecdotalism and descriptivity of much populist verse does not in itself amount to anything I’d call ‘poetry’.

Has poetics become too philosophical? Too political? How do you deal with this in your poetry, or are you indifferent (immune?) to it all. . . ?

I can’t remember when I last read a book on poetics. In the 70s and 80s I did read Barthes, Foucault, Derrida and related work, and I’m sure you could trace the use I made of that and perhaps still do as a kind of background. But the philosophy which I consciously dwell on is what I learnt as an undergraduate a decade before, the Presocratics, Hume, Philosophical Investigations. The Presocratics for the impacted fragment, Hume for sceptical good nature, Wittgenstein for his attention to language as it goes about its business. That’s what I was trying to acknowledge when I wrote ‘Wittgenstein’s Devil’ although that poem is also a response to Steve McCaffery’s writing. Steve has much more enthusiasm for critical theory and contemporary philosophy than I have, at the same time as we share a number of preoccupations—that poem of mine is driven by the similarities and differences.

Does poetry still matter? Is it still worth the investment? One is liable to devote a whole lifetime to poetry, a whole lifetime to the study of it, we become, some of us, and in our various ways, scholars of our tradition . . . is it worth it any more?

We’re talking about poetry because it still matters to us and maybe a few hundred people of our acquaintance. I admit I’m less convinced now than I used to be that it can be made to matter or even be much noticed in the big wide world. Perhaps it will, we can’t know that, must just do what we do and want to do. ‘Literature’ in current parlance practically always means the novel, and usually novels of largely narrative interest not striving for any intensity of language—the very thing for which we read poetry is somehow regarded as off the scale of common appeal. I’m depressed by that, and even more when I find the same low intensity in poetry itself.

Has it diminished, the degree of intellectual power that poetry is expected to exert? (Have poets given up on any such exertion. . . ?)

Perhaps there’s a shortage of curiosity. One reason to mistrust the ‘avant-garde’ is that some of its exponents seem no less conservative and no more thorough-going than the self-proclaimed ‘mainstream’.

How seriously do you take poetry, do you believe what you are doing is “important,” and, does poetry impart knowledge to the reader, besides just a series of details and descriptions, decoration?

Poetry works through a species of thinking unlike any other and what value it has lies in that.

“A species of thinking unlike any other. . . .” That’s quite a statement, and I think it’s humanistic. I wonder, though, if it’s just a specialized mode of cogitation or, maybe, a special mode of consciousness . . . but I don’t think it’s democratic (that is to say, equally distributed), and I think its value is, in good part, in that it is not democratic. But isn’t this to see of the poet and to give of the poet a special place in society, in humanity? If I may play devil’s advocate, granted this “species of thinking unlike any other” has value in and of itself, but what does it produce, what effect does it have, what does it tell me about myself and about how I should live my life. . . ?

Instead of ‘species of thinking’ I could have said ‘a use of language unlike any other’. A long time ago, in a rather gnomic essay called ‘On Poetic’, I tried to get at this via the standard logico-philosophical distinction between necessary truths and empirical statements. It seems to me that in so far as poems make statements at all those statements are empirical in form but function as it were in suspension from the empirical. Poetry very rarely employs ‘necessary truths’ but if a poem is any good its parts are held in a kind of necessity which is determined by various devices but essentially rooted in unusual linkages of sense enabled by sound pattern. That’s why a poem exists in only those particular words and in that particular order; and is also what allows a poem to make jumps in thought impossible by any other means. The poem opens out language, reveals what language holds within itself. Anything else it does, didactic or not, is secondary and I assume depends pretty much on what the reader does with it or takes it for.

Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo.” You must change your life. I think today we put the poem under such scrutiny, that we subdue the poem, we subject it to a sort of vivisection (a “deconstruction”), whereas the poem should put the scrutinizer under scrutiny, and thereby tell us about ourselves—we should see elements of ourselves in the poem, such that we understand and can adjust. Is this not the true power of poetry and of literature?

I try not to generalise about what ‘we’ do but agree that the arts—humanities—‘do’ something which the merely utile doesn’t.

When you speak of “the anecdotalism and descriptivity of much populist verse” and say it “does not in itself amount to anything I’d call ‘poetry,’” I must then ask, what do you consider to be the (worthy of salvaging or otherwise plausible or tenable?) poetic elements of poetry, and where are they located (if such is the case) in the postmodern poem (or if not “the postmodern poem,” then in your own poetry or in any poetry that in your opinion is important, is credible or is legitimate, authentic, real); and this, please, in light of the “free play of the signifier,” and of the text as a form of practice and of “the diversity of practice”? That “local wreckage,” is it culture? Is it modern poetry?

I haven’t got much more to say about the ‘poetic elements’ than I’ve already said. I don’t make any sharp distinction between poems written in different periods; the variance in technique and treatment is incidental. The signifier hasn’t suddenly been freed, it’s just found itself some fine new playgrounds.

By ‘local wreckage’ I was only trying to distinguish the environments in which American and British poets write, to suggest that we have different things to cope with. In our case ‘wreckage’ came to mind—the clichéd and pompous rhetoric of a post-imperial power, the failure of any rigorous historical sense in linking particulars, and so many particulars—a mere time-bound clutter piling up on itself in a very small country which once decked itself out with the fancy trappings of the Roman Imperium—now caught in endless vacillation between demolition and preservation. That’s our context, American poets have another—no happier, I’m sure, and I’m not silly enough to attempt to define it.

One of my favourite recent books is Laurie Duggan’s Crab & Winkle. Laurie is an Australian poet now living in England and the book is a fragmentary poem-journal recording his first year here. He’s wry and accurate, and for a native reader he turns the familiar inside out. At one point he asks ‘is it the case that everything here is like something else? Is this why standard English poetry is so fond of the simile?’ Yes! The observation probably hit home because I’ve always felt an antipathy to simile without ever identifying cause or reason. We have to be alert and careful with these things and I tried to reflect that in the title of an early book, Perspectives on the Reach, which had an epigraph from Richard II: ‘Like perspectives, which rightly gaz’d upon, / Show nothing but confusion; ey’d awry, / Distinguish form[.]’

“A poem’s autonomy overrides its subject.” In what sense, “a poem’s autonomy”?

A poem is a poem, no more, no less. It may carry implications and connotations outside itself but to identify it with those extra-poetic dimensions is to mistake its nature. But the mistake is so often made, usually for sentimental reasons—the Adlestrop Syndrome.

Here’s a question, you can dismiss it or you can grapple with it any way you like: However did the ungrammatical come to seem poetic? (It seems to me maybe Stein had something to do with this, and Cubism, too.)

I doubt if any poet has paid so much attention to grammar as Stein, and that’s why she could be so free with it. And exciting. The doubt only arises, as usual, with her imitators—the assumption that being ungrammatical is sufficient in itself. It’s the same with any technique or device: not whether it’s good or bad per se but where and when to use it.

“Ey’d awry!” Is that not “The Poet’s eye, in fine frenzy rolling,” a species of thinking unlike any other? I’m not certain your sense of “gnomic,” but in folklore gnomes were believed to have knowledge of hidden treasures. . . .

No fine frenzy intended. I felt at the time and still do that ‘ey’d awry’ nicely expresses my liking for looking at things from odd angles, preferably somewhere round the back, if I’m to write about them. I’m sure Michael Peverett didn’t mean me to like his remark that my ‘writings are the dark side of the moon’ but I can’t think of any better place for a perspective.

What, then, is your sense of the poetic? Is it just syntax, or, is it only found, in the diction and in the arrangement of the words (that empirical in form)? Certainly poetic rhetoric is to be appreciated in its own right, but what about the semantic (that which exist in suspension from the empirical)? This, and the thought on the simile, bring to mind the whole consideration of “a false parallelism between the grammatical and the semantic.” I understand there is something “false” in the identification of one thing with another, but isn’t that how semantic changes occur, and how language is increased? Should poetry no longer give us, or strive to give us, similes, and for that matter, metaphors? Those “extra-poetic dimensions,” it seems to me that that is precisely where I should hope to locate, and identify, the nature of the poem (or perhaps I should say, of my own poem). How could I be so mistaken? What is your sense of those “extra-poetic dimensions”? Have you, yourself, ever experienced “Adlestrop Syndrome,” and have you ever written a poem while in that state?

In ‘On Poetic’ I wrote ‘Poetic is language compressed to the maximum degree.’ That seems a little over-zealous nearly thirty years later but I stand by the notion of ‘compression’. By ‘poetic’ I meant the kind of thought or use of language that makes poetry possible and distinguishes it from other modes of writing; in practice it’s achieved by a synthesis of sense, sound and shape (even where the shape has the appearance of prose—the distinction is not formal in that respect). The synthesis means that one can’t easily isolate the semantic element from the syntactical or any other—or rather if one does then the whole thing is liable to fall apart.

Sometimes I’ve tried to come at this by a different route, the notion of ‘the wordland’. The wordland isn’t language, it’s the territory in which language or rather languages exist. The ground of language. To write poetry is to explore it in a very particular way, relating conspicuous landmarks to its hidden places. And you never know who you’ll bump into when you’re there.

I referred to ‘extra-poetic dimensions’ just to distinguish the poem itself from any implications or connotations it may carry and of course those will vary from reader to reader and at different times. One could even argue that they vary the more the better the poem—Shakespeare’s sonnets, for example, or in the more recent past Bunting’s Briggflatts—the best poems are the ones you read a hundred times and every time seems like the first. There’s also the strange but indisputable fact that poems become more or less legible over time—to many 21st century readers much 18th century poetry is virtually illegible, just as much 17th century poetry was to 18th century readers (remember Johnson on Cowley and his coinage of the expression ‘metaphysical poetry’ as a term of abuse). The degrees of compression used or fashionable in different periods may have something to do with this—certainly the extreme compression of ‘modernist’ poetry accounts for the resistance it still receives.

I don’t mean to be prescriptive about simile—it doesn’t work for me as a poet but I can appreciate it when others use it well. The same goes for any other device, I find some more useful than others. What struck me about Laurie’s observation was its accuracy about a certain aspect of English life and how it lends itself to simile all too easily, and easily misleads. In the late 1970s there was a school of well-publicised English poets known as the ‘Martians’ who specialised in simile—of the ‘light switch looks like an owl’ variety—I guess I wasn’t the only one who suddenly found simile quite odious. You could see this searching for likenesses as a refusal to see things as they actually are—or, if that’s too philosophically tendentious, at least as a refusal to talk straight. Which is much the same impulse underlying political jargon and journalese.

I doubt if language ‘increases’ more by poetic devices than it does when it’s out on the streets.

The Adlestrop Syndrome is an affliction of readers rather than poets. Here’s an example: Joan Bakewell recently chose ‘Adlestrop’ when asked to nominate ‘the best poem by a living [sic] poet’. She commented that it ‘is quintessentially English. It catches the peculiar air of an English summer, blowy with seeds and dust. I can’t stop at an English station without thinking of it. It makes me love England the more.’ This is to regard poetry as much the same thing as holiday photos. And sadly it’s what many people do expect from poetry: a measure of reassurance, a ready fix on some normative emotion. But what use is poetry—and what else can be meant by ‘emotion’—unless it disturbs?

What do you think about romanticism—as a movement or as a Zeitgeist or as an impulse—and do you identify at all with the romantic poets, say, for instance, Keats, Shelley, Coleridge, Wordsworth. . . ?

Blake was one of my earliest enthusiasms. I had to learn a lot about Shelley’s life before I grasped his poetry. Recently I’ve been interested in some of his occasional verse, unexpectedly complex in places. Coleridge an endless fascination. Byron mostly for his satire. Beddoes is the Romantic I feel closest to in some inexplicable way. One of the books I’m most pleased to have published is the later version of his Death’s Jest-Book.

Here is a quote from Herbert Read, from his essay, Surrealism and the Romantic Principle, written in 1936 (and I emphasize, written in 1936):

“To identify romanticism with revolt . . . is true enough as an historical generalization; but it merely distorts the values involved if such revolt is conceived in purely literary or academic terms. It would be much nearer the truth to identify romanticism with the artist and classicism with society; classicism being the political concept of art to which the artist is expected to conform.

“It may be as well to forestall at once the criticism that on this showing the artist is merely the individualist in conflict with society. To a certain extent . . . this is true; the mental personality of the artist may be determined by a failure in social adaptation. But his whole effort is directed towards a reconciliation with society, and what he offers to society is not a bagful of his own tricks, his idiosyncracies, but rather some knowledge of the secrets to which he has had access, the secrets of the self which are buried in every man alike, but which only the sensibility of the artist can reveal to us in all their actuality.”

Any comments on this quote?

It makes me feel a bit queasy. Why did Read feel he had to bend over backwards to reassure his audience that these maladapted treasure-hunting artists want ‘reconciliation with society’? Artaud was nearer the mark: ‘If there is a culture it is always alive and it burns things up.’

There are forms that have dramatically impacted the way poets write, and that have thus revitalized poetry (the making of poetry), for instance the sonnet and the sonnet cycle (from the Petrarchan to the Spenserian and the Shakespearean, from Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Dante Gabriel Rossetti to Rilke and to many of our contemporaries), and for instance, blank verse, and free verse (vers libre). The individual poet applies his talent to these forms and, if he is good enough, thus the various epitomes, or, representative instances of the form. Today, it seems, there is the collage form (if it is indeed a form, or let us say for question’s sake). And there is the form known as “recontextualization” (—although here it seems “form” is synonymous with “practice”). I’d like you to comment, please, on the impact that the collage poem and that “recontextualization” are having on poetry and on the way poets are writing today—and especially where concerns collage, do you see this at all to be in the same class as the sonnet and as blank verse and as free verse?

I’d see collage as a practice or technique rather than a form—after all, it can be made into any of the forms you mention. It’s true, isn’t it, that it’s one of the few techniques which poetry has adopted or adapted from the visual arts, and the one distinct area in which the visual and verbal continue to work side by side? In recent years visual artists seem to have made increased use of text, mostly found and relocated, but in much of the work I’ve seen the text lies quite flat, I suppose deliberately so and relying on an easy irony. But I notice the same tendency in poetry too. The poem as ‘document’. There seems a broad spectrum, from ‘conceptual’ poetry to the schematical procedures of Oulipo, and a lot of it doesn’t engage me very much. No document or schematically derived text becomes a poem without a process of transmutation. The old alchemical term is vital here. It’s the same problem really as with merely descriptive or narrative writing—it’s not the description or the narrative which makes a poem but the transmutation of it.

A very obvious shift has come about through the internet. When we had only printed sources it was largely by chance that we’d hit on useful material—chance and the fact that we were print addicts in the first place. The possibility of feeding any phrase into a search engine and immediately being offered thousands of source texts and routes changes everything. You don’t need to be half a poet to register the not-entirely-by-chance ‘poems’ (or anti-poems) thrown up. It paves the way for a whole new genre of ‘machine poems’—the anthologies are already appearing—and as ‘language objects’ they have some interest. But what’s more interesting is that one can (I hope) always tell when a real human poet has been at work. Perhaps that will change and any fool will be able to create a St Thomasino or Halsey poem indistinguishable from anything you and I have written. That will be the moment to throw in the towel and spend more time in the garden.

At the beginning of this interview, you mentioned, “the imaginative realm where I dream I belong.” May I ask, what is this “imaginative realm” made of—is it an emotion, is it an idiom, is it a goal, something you are creating as you go along (and so something that is perhaps forever out of reach)? Is it both the art and the poetry. . . ? You seem to move effortlessly between the “workaday and taxable” world, the world of everyday habits and to-dos (Is this the world of “Broad Street”?), and the fabulous, the phantasmagorical and exotic. There exists here, in both the art and the poetry but especially in the poetry where we find the narratives of these things, there exists a very real Halsey Physiologus, populated by fabulous beasties, fabulous conjurations . . . . I think I can say that as a reader (but should I qualify that with: as an American reader?), I definitely find there to be something exotic about “Halsey,” and this might be that perception enlivened by cultural difference that you mentioned earlier, and what’s more, for me, there is definitely an escapist element to it . . . and I think I mean by “escapist” something “dreamy,” “charming,” this something “exotic” about “Halsey.” Does the creation of your poetry hold such an element for you (although I would imagine it is something complicated and intimate)? You know, very early on I acquired the notion that poetry ought to give you, to give one, the feeling, or, a feeling similar to, of playing hooky from school. (I know that sounds ironic, how something that is associated with the classroom, and so as such can be a drag, when approached on its own can be liberating—and somehow, I think it is due to that perspective, that “dark side of the moon” perspective!) Maybe that is that “disturbance,” my own personal “disturbance.” (And this is not a “reassurance”—and not just any poetry can do this to me.)

You ask, “But what use is poetry—and what else can be meant by ‘emotion’—unless it disturbs?” Does poetry teach us by disturbing us, or is the disturbance an end in itself—and if so, is that the “poetic experience”? Can poetry that disturbs also be liberating? Is there any moral instruction in your poetry? Should there be moral instruction in poetry generally? Can poetry be moral (what I mean is, can it impart a lesson, an instruction) without being didactic (which is to say, without intending to, or, without explicitly stating what the lesson is)? Do you care what the reader does with your poem or what he takes it for? I understand you don’t want to “generalise about what ‘we’ do,” but . . . we’re not just machines building ant hills, are we? (Is this question, that I have just articulated, an “ant hill”? Is this a fair question to ask a poet?)

I think one can’t be exotic to oneself, fortunately or not, but you’re probably right that I’m more willing than a lot of poets to use remote or (I’ve heard it said) obscure material. Sometimes there’s a personal association, sometimes not. It’s practically always some combination of words that excites me to write—sometimes a single word—and as with collage elements they’re usually ‘chance’ finds—in a conversation, on the radio, in a book maybe picked up at random. I prefer not to determine in advance where these caught words will lead, I do like a surprise. If the poems are ‘escapist’ I’m not sure what they’re escaping from but I hope that even their further reaches maintain some contact with the workaday world. I come across a lot of contemporary poems which never seem to stray from what I suppose their authors regard as a common reality—‘things seen’, available to everyone to see and narrowly reflect on—I’d call that ‘escapist’ in its refusal of—what?—‘vision’ in the broader sense? Is that too grand? Must we call it ‘context’? But of course there has to be control, it’s unwise to let words do anything they please—that only leads to a different narrowness.

I was partly making an etymological remark about ‘emotion’, that it derives from the Latin emovere, ‘to disturb’. A poem which doesn’t disturb, not in what it says but in the way it says it, cannot raise emotion although it can and often does create a simulacrum of familiar feeling, which is what sufferers from Adlestrop Syndrome crave most of all. How can a truly disturbing poem not be liberating? I hope the satirical undercurrent in much of my work is fairly evident, and where there’s satire there’s politics—things to do with the ‘polis’—and so morality. But a satirist has to stand outside any party point of view, as Swift so clearly articulated having learnt it the hard way—he otherwise becomes a mere propagandist. It’s futile to care what anybody thinks of your work, partly because it’s incalculable. I tend to have a small number of readers in mind when I write, mostly people I know fairly well. And sometimes I write a poem convinced that one of those people will really like it and then it turns out that s/he loathes it but loves another thing I thought was entirely up another street.

You said, “I don’t make any sharp distinction between poems written in different periods; the variance in technique and treatment is incidental. The signifier hasn’t suddenly been freed, it’s just found itself some fine new playgrounds.” I agree with that proposition, and I think I can point to it as the defense for a sort of experiment I conducted, and that is I assigned a reading of the Andrew Marvell poem, “To His Coy Mistress,” and then followed it up with a reading of your poem, “Broad Street Drag ’87.” It was immediately comprehended the relation of the two texts, and not entirely on the basis of “content” or “story,” but as narratives that, despite their differences in form and idiom (—for example, your word, “drag,” in the title), as narratives that successfully portray a certain tone and tenor and frame of mind. And moreover it was immediately accepted the perspective that can see how your poem is in historical-chronological relation to Marvell’s, this in regard to the consideration of the degree to which a poem is conscious of itself as a work of language. (I think that if I had the chance to mention that to Marvell, he’d reply that I was stating the obvious. But somehow it has become what I consider to be a prominent if not primary consideration for poetry today, and that is the foregrounding of the poem as a work of language.)

Look, forget what I said about not caring . . . even if you’re the only reader who thinks anything I’ve written can stand beside Marvell . . . [long pause]. We all get enthusiasms for this or that poet and some last and some don’t—but I loved Marvell when I first read him in my teens and I’ve never wavered. He’d know exactly what you mean by the ‘poem conscious of itself as a work of language’—he’s strangely ‘modern’ in that respect, as also in his rough edges—‘incorrectness’—which Johnson so despised. He shows above all how you can take a stock theme (poems to coy mistresses must be as old as poetry itself) and lace it with all manner of references and allusions—and make the poem work regardless of whether the reader understands them or grasps exactly why they’re there. I remember an Empson essay in which he speculates that the line about the conversion of the Jews refers to Millennialist expectations during the English Revolution—if the Millennialists were right then Marvell wouldn’t have long to wait . . . and it’s not whether this is right or wrong but the way the reference creates a luxuriant spaciousness within the poem—and Marvell does this again and again. Sometimes he seems to be conducting a private argument with himself about some arcane matter which is quite remote from his ostensible subject—Neoplatonism, for example, in ‘The Garden’—there are few better examples of poems which work on different planes simultaneously.

And I suppose ‘Broad Street Drag ’87’ does this, or attempts to. It’s rooted in a commonplace theme—‘what I see outside my window’—which for many years was Broad Street, Hay-on-Wye, from my desk in the Poetry Bookshop. There are Broad Streets in many country towns here—literally broader than the other streets because they’d be used for markets, and so they have that commercial connotation—and often, as in Hay, with grander houses for the wealthier locals. So in the poem what I see from the window isn’t the street itself but the hub of trade, at a time when all sorts of questionable deals were going on, affecting both the commerce of the place and its actual fabric. The ‘green middle’ / ‘good muddle’ refers to a long-established orchard which had been cut down and built over with dreary houses but as reader you don’t need to know that. The core of the poem is how one stands as a ‘self’ within all this, with uncertain continuity and largely as a token of what you’re ‘believed to believe’. I guess that’s very Marvellian, although Marvell’s inscrutability was played out on the most public of stages. By the way, isn’t ‘drag’ a splendid and tough little word to carry so many meanings? The jazz dance, as Jelly Roll Morton used it, was foremost in my mind—but half a dozen other connotations would do just as well.

Broad Street Drag ’87

Right out of place and left standing

by your word you are speechless,

sure, as the one I was

half an hour ago

but let’s not

name names: what was bought

must be sold at a loss which ensures

the raised price

will keep rising

and the limit

reach back into the former restriction,

buying in and selling out:

‘consolidation’ was the word

the year after ‘in-filling’

was the form

thoughts took and filtered

out the green

middle of the town.

The good muddle.

Built over with flush brick,

bought out but coming in,

I’d call that unearned income.

It’s what you believe

you are believed

to believe and if you’ve heard it

from three different

sources on consecutive days

you’ve been warned.

In 1995 you published a highly conceptual little masterpiece entitled, The Text of Shelley’s Death. The book is divided into three parts: “The Text of Shelley’s Death,” “Reversions on the Text,” and “Towards an Index of Shelley’s Death.” I read the titles, but did not give any special weight to “index.” (I should capitalize that “i.”) “Index.” When I came to this part, the third part, of the book, what I found and what I read was totally unexpected. I read this index, this “I”ndexing, the Indexing of these lines, as an enshrinement; and more, as an apotheosis. And the whole thing made sense to me.

‘I’ndex! I hadn’t thought of that, it almost sums up the book in one word! It’s the largest-scale multi-voiced—multi-I’d—work I’ve attempted. I’ve sometimes thought it’s one long endeavour to show that the opening sentence is false: ‘Everybody knows the text of Shelley’s death.’ It’s not only the first sentence of the book but the one I wrote first; you can read it with the stress on any of its words to deliver a different meaning and not one of those meanings is true. Above all there’s no ‘text of Shelley’s death’—there are only these many I’s telling a variety of mostly incoherent or at least inconsistent stories. The ‘index’ was an afterthought. Originally the book was only going to consist of the title section. Then I felt something more was needed and wrote the ‘Reversions’. But I still had a notebook full of unused lines drawn from Shelley’s poems, manuscripts, cancelled drafts, etc and it struck me that I could organise them as an ‘index’—which of course is no more an ‘index’ in the conventional sense than the ‘text’ is a text. The fact that it finally reads as an alphabet poem was one of those nice little surprises. It can even be performed in two voices—Gavin Selerie and I premiered it just a few weeks ago.

Finally, for the reader coming to the poetry of Alan Halsey for the first time, what should he read first, where do you suggest he begin (besides “Broad Street Drag ’87,” that is)? Or, is there anything on the horizon that you’d like to alert us to?

I’m sure Marginalien will remain my most extensive collection for a long time. Five Seasons also recently published Lives of the Poets, which I began in 2000. The publication doesn’t mean I’ve finished writing ‘lives’, which seem to have become a genre of their own, brief highly-concentrated poems which try to encapsulate a poet’s life where s/he really lives it, in the wordland. And earlier this year Ahadada published Term as in Aftermath which collects poems from 2005-7, including the complete Looking-Glass for Logoclasts—a title and sequence I owe wholly to you for calling me a ‘logoclast’ in the first place. I’ve never fully understood what you meant but perhaps for that very reason it’s been fertile ground and I thank you for it. In its response to your comments it almost feels like a collaboration and I do enjoy collaborating. The first extensive collaboration I did, Fit to Print with Karen Mac Cormack, allowed a deep shift and new freedom in my writing. There’s always a danger of being trapped in your own short circuits. It’s good now and then to inhabit another writer’s word-world, with a licence to steal.

Thank you, Alan Halsey.

Copyright © 2010 Alan Halsey & Gregory Vincent St. Thomasino

Alan Halsey (1949- )

Alan Halsey at Archive of the Now

Alan Halsey at the British Electronic Poetry Centre

Alan Halsey at Coach House Books

Alan Halsey at Poetry International Web