Susan Bee

interviewed by Gregory Vincent St. Thomasino

2011-2012

Self-Portrait, Susan Bee (1964, etching)

I want to ask — and specifically with regard to the artist — about the “act of creation,” the act of creation as an aesthetic experience for the artist. And this as something personal to the artist, as something she knows peculiarly as the artist, and as an artist. This experience both is and accompanies, say, “discovery,” “revelation,” “disclosure,” this is that point at which a work begins to suggest itself, the “a-ha” moment, but more than that: there is a dramatic or emotional or even sensual element to it, a frisson. What is it like for you when you are working, when it is working, when you are in the midst of it, when you enter that zone of concentration, of originative thinking? For instance, would you describe it as “existential,” as “accessibility,” as “inspiration”? Or: is there indeed “an aesthetic experience” for you in your act of creation? And if so, will you let us in on it?

This is a difficult question to answer. I have different approaches to getting into the mood to work. Sometimes, I respond to an assignment, as in this case of the interview, or when I’m asked to illustrate a book by a publisher or poet. Also, on occasion I’ve created work for a specific group show.

Sometimes, an image just comes to me, but more often I do some research or drawings. For instance, for my next show [Recalculating: New Paintings, A.I.R. Gallery, New York, 2011], I’ve been working on a series of paintings that are based on stills from films, mostly film noirs. So I’ve been sketching out the images as outlines on the canvas and then filling in the drawings with oil paint and color. So the inspiration comes after the initial impulse is followed. Then I let go of the film still that the painting is based on and go with my personal response to the image, emotionally and in terms of color and shapes. I suppose that is what is referred to as the flow. I can work on one painting over a long period of time, changing the colors, layering the paint, and exaggerating and revising certain linear elements. So a transformation takes place and I enter into the image.

I have sometimes experienced “the ‘a-ha’ moment,” and I agree that “there is a dramatic or emotional or even sensual element to it, a frisson.” However, I’ve learned to move beyond that moment. I mean that experience has taught me that the work produced in the moment is not always that interesting and that often when I go back to look at the work produced in those moments those works need a lot of retooling. The “a-ha” cannot always be trusted to produce a great aesthetic experience for the viewer. The rational and judgmental mind needs to come into play. Sometimes, I look at the work upside down or in a mirror to get another view, or I just leave the work and come back to it on another day with a fresher eye. Often, I will ask another trusted viewer, an artist or poet, to give me some feedback on what works and what doesn’t.

My work also feeds on itself. Certain images recur: natural elements like trees, sailboats, and mountains and sometimes one work seems to call out for another one created in a similar mode. So that the discovery comes with the process of creating and one images leads to the next one. It is a fairly organic process, where certain themes start to occur and then are elaborated on. I once wrote that I am filled with images and that seems to be true. Images just seem to pour out of me.

Dreams (and the unconscious). Dreams and art. They’ve a lot in common, the dream (its visual images, its emotional content, its conceptual phenomena) and the work of art. In regard to both the dream and art, we can say that “content” is represented not realistically but psychologically. And for instance, and even in strictly mechanical terms: there is distortion, condensation, symbolization — the representation in terms of symbols, and in terms of difference, in terms of opposites. Both the dream and the work of art speak in a language of symbols (in figure, in color, in gesture), both may be said to reflect the fundamentally subjective nature of the mind, and both may be said to be the product of a psychic discharge. And for instance — and here I’m jumping to an extremely sophisticated proposition — the dream and the work of art both specialize in disguise. Do you ever talk about your dreams in public — or, isn’t that exactly what artists do, or rather what they do when it’s working. . . ? What role, or roles, do dreams play in your art, and in your life? Do you keep a dream diary? Do you “cultivate” your dreams with, for instance, melatonin? Do you consult a dictionary of symbols (pictorial and otherwise)? Do you specialize in disguise?

Somebody asked me about the dream question for a book on artwork based on dreams. I replied that the painting that was featured in my last show was presaged by a dream. The painting is Eye of the Storm.

Eye of the Storm (2007, 48 x 51”, oil on linen)

Here is what I wrote about the painting:

As to the dream, it appears in the visual realization of the painting. The storm, the vortex, and the eye and the sailboat with the lone girl in it. I had the dream or vision in May 2007, when my father was very ill. Then painted the painting based on the small pencil sketch I did when I woke up. I also used to create the painting: computer images of actual hurricane “eyes.” Unfortunately it predicted or presaged two traumatic and horrible events in my life. The sudden death from a fall of my 87-year-old father, Sigmund Laufer, in October 2007 and the death by suicide of my 23-year-old daughter, Emma Bee Bernstein, in Venice in December 2008.

I have been using a lot of images of angels, saints, and fairies in my paintings. In Jerry Rothenberg’s Burning Babe (Granary Books, 2005), I used much religious imagery to match the images in the poems. Oddly that imagery and most of the angels I use are Christian or Buddhist icons. I am Jewish, but I have also used Kabbalistic imagery, as in my “Philosophical Trees” series. So I am inspired by all sorts of religious, mystical and spiritual imagery. In addition, I am interested in folk art and naïve or outsider art. I have an ecumenical approach to my aesthetic influences.

In terms of dreams, I often dream about bigger studios or problems in my studios, such as floods, which in fact have occurred. But I don’t paint based on my dreams. My imagination is sufficient and pretty frisky on its own, so I don’t feel a need to consult my dreams, which are often fairly mundane.

I definitely create works that have a symbolic over layer or under layer and are based on my unconscious impulses. Sometimes, I don’t understand all these impulses myself. I appear as a character in a lot of the works, so does my husband and son and daughter. Many of the most recent paintings refer to my daughter or are based on images or paintings that she loved.

I don’t know that I use disguises, just stand-ins for my feelings. The paintings are open to a variety of readings by viewers, which would differ from how I would experience them. I love the open-ended nature of art. The viewer is free to read into the artwork whatever they are seeing that day.

Generally speaking, and speaking from my own experience, I think it is the case with children that their first aesthetic experience — which is to say their first encounter with art, or with the stuff of art, which is to say the application of color — is, quite simply, by way of coloring — coloring books, finger painting (and how about that smell of the finger paints, is not the child enjoying a synaesthesia!). . . . I know for myself, in regard to those coloring books, it was not immediately apparent to me that you were supposed to color-in the outlines (I know this ’cause I asked my mother about it), my natural inclination was more toward “action painting” * (as in moving my whole arm instead of just my hand), and curiously enough my favorite book was Harold and the Purple Crayon (in which little Harold is forever drawing the outlines of figures!). Which is to ask, would you say something about your early education in the (visual) arts (were you an artistically endowed child?), and about the history (the evolution, if you will) of your perspectives — and/or were you “coloring,” and did you have a “Harold and the Purple Crayon” of your own?

* I think for me, it (artistic play) was always an expression of emotion, or of some sort of psychic (or, visceral) discharge. I’m reminded of cave painting, rock painting. I’ve heard it said, and I think there’s something to it, that these places are like churches, that they are sacred places, places for reverence and contemplation and meditation. I wonder at what point the expression went from being the “simple” documentation of the surrounding nature to being the revering of that nature. . . . I don’t want to commit a fallacy (I’m not sure there is a parallel between the development of an individual mind and the development of the “mind” of all of humanity), but I think there is a point for the child at which he either stops doing it or now does it with a newfound deliberation. I think this is the point of self-consciousness. . . . I think even in the most formal expression, say in cubist portraiture, there is, beyond the expression of the form, there is something being revealed, something being told, about the person (and about the artist, in that this is what she sees and chooses to reveal). This is not to say an expression of form is in itself empty of content — for sure, the “form,” in itself, can be quite beautiful.

Both my parents, Sigmund and Miriam Laufer, were artists. So I was raised in a household where art was the main mode of expression. I was always given paper and crayons and pencils and paints to draw with and was encouraged to draw as much as possible. Also, I was taken to museums and galleries a lot as a child. I grew up a few blocks from the Met and it was part of my education to wonder around the galleries there from a young age. My mother had gallery shows and my father did too, so I went to their openings and hung out with other artists’ children in the summers in Provincetown. It was a bohemian atmosphere that surrounded me.

I also studied as a child at the Museum of Modern Art painting classes for children, where they encouraged a kind of expressionism, sort of like fingerpainting, with strong colors and forms. I won a contest in second grade for the best children’s painting. It was a painting of me with a dog (I think it was oil on paper that I painted in my mother’s studio) and I was interviewed by David Brinkley, on the Huntley/Brinkley Report.

Interview of Susan Bee Laufer (at age 9) with David Brinkley on the Huntley/Brinkley Report, NBC, 1961. In the background is her oil painting of "Girl with a Dog," at Galerie St. Etienne, NYC.

There was an exhibit at Galerie St. Etienne and the interview played in movie theaters as a short with a segment about a painting chimpanzee and also the French artist Niki Saint-Phalle, who shot her paintings. In the interview I critiqued my painting, which I didn’t think was very good. I also asked for a dog, which my parents got me after this was broadcast on the national news.

I also loved coloring books and paper dolls and I would play with little plastic toy figures and make imaginary landscapes. I used paper dolls in many of my paintings from the 80s and 90s, when I was influenced by the art and toys of my own children.

The abstract expressionists were very interested in children’s art. And as mother was tangentially part of that circle and had grown up in a progressive children’s home in Berlin, she always encouraged me to be as expressive as possible in my artwork. She would take me with her to her studio and sit me in the corner with paints and paper. My father, who was a printmaker, took me on weekends to Pratt Graphic Center and gave me tiny plates to make etchings.

As to the caves, I have visited many in France and Spain and they are like cathedrals. The art on the walls is amazing and vivid and sophisticated and alive. But that is another subject.

Psychologists who research creativity inevitably come to consider the dichotomy between work and play, and how this dichotomy can be adverse to creativity, and then how work and play need not be considered antithetical. I wonder, has this ever meant anything to you, has it ever been a problem (such that it, this dichotomy, could stifle your creativity)? And when I look at this little girl, in this situation, I wonder: just what is she showing, is this her play or is this her work? You obviously had the understanding that your play had value beyond being play, and I take it you’ve been at it ever since, or, has there ever a period when you did not create, or periods when your “play” was not evaluated? I see in your work, or such is my impression, and I don’t think I’m the only one, I see something implicitly the product of a child’s perception, or, perhaps better, the as seen through a child’s eye. I’d say this not only accounts for the visual distortion, but for the freedom of movement, vertical movement, the insight that penetrates uninhibitedly, and I think this accounts for why your work is more psychologically real, than real. Is this your style?

I was encouraged to take myself and my artwork seriously as a child. Yet, I always played a lot whether out on the street or in the playground, in the park, or at home. I was a very playful child with many friends. In fact, I was always running around outdoors and indoors. I had a very extensive fantasy world and I was very much given to daydreaming and to engaging in the realm of the imagination. I think what David Brinkley found so funny about the interview with me was how critical I was about my own painting and how disturbed I was by my failure to really portray the dog properly.

I was interested in drawing from a young age and spent many years drawing from the nude starting at about age 12. I was very self-critical about my inabilities to get anatomy and perspective right. Around age 13, I realized I might actually become an artist, when my friend, Toni Simon, suggested that might be my fate. Up to then, I had not really considered that I was headed in that direction.

The only times when I have not created artwork was when I was depressed or sick. I really create all the time. It is just like breathing to me. I do like to maintain a childlike approach to making art and I do consider art making like playing and yet it is like work too. Practice is important and so sometimes I just go to the studio and work, even when I am not inspired, but just feel like drawing or creating in some way. I also look at a lot of art and when I feel uninspired I like to just go outside and wander around in nature or in the city as a flaneur.

I was always a hard worker, that was part of my upbringing as a child in an immigrant family. There were household chores and work for pay as soon as I was able to. The traits of responsibility and my practical nature and perseverance are somewhat at odds with my sense of wonder. One of my friends described me as having my head in the clouds and my feet on the ground.

As a cultural product, what does your work say about our culture — whether “culture” as in culture at large, or as in a folk art, or as in an ethnic identity? Or, do you aspire to making social commentary? What role does the artist play in society? What makes art valuable?

I am making art from my own perspective as a middle aged, white, heterosexual, secular Jewish woman. I am also a wife, mother, teacher, book artist, designer, editor, and writer, who lives in New York City. So from the point of view of ethnic or cultural perspectives it is hard to escape the ethnic and gender limitations of your particular body and setting.

On the other hand, my imagination has free reign and I can imagine myself in different settings. In my art I can look backward and forwards and travel outside of my own narrow circumstances. So I think that the imagination carries me outside of my own perspective. I look to the historical past, other artworks, films, ads, popular culture, folk art, and other sources to find further resources to explore in my artwork and life. I try to stay open to other voices and perspectives that differ from my own.

I hope the artist plays a positive role in society. I have tried to engage other artists and poets and a broader public in my work as a co-editor of M/E/A/N/I/N/G, in my collaborations with poets, in my work with the feminist gallery, A.I.R., and in my teaching. I think it is important to act ethically and to attempt to inject positive energy into any situations. But, I realize there is plenty of injustice in the world and that often you have to fight to have your voice acknowledged.

In my work, I do comment obliquely on gender relations and on the relationship of the individual to the natural world. I am interested in the romantic view of the individual in the world, framed as we are by nature and other people. Most of my recent work is figurative and it deals with the persons ensconced in an environment or in a relation with others. These are not realistic works, but more existential and situational. I experience the individual as a mutable being. In other words, we are not alone in the world, but inhabit a world filled with other people and creatures and with the ghosts of the past and images of the future haunting us.

Other people determine if my art is valuable, if it has something to say to them. I hope that the paintings will provide solace or insight or beauty or can bring something new to the viewer. However, I cannot predict the effect of my artwork on others, and I am often surprised by an insight or reaction of a viewer.

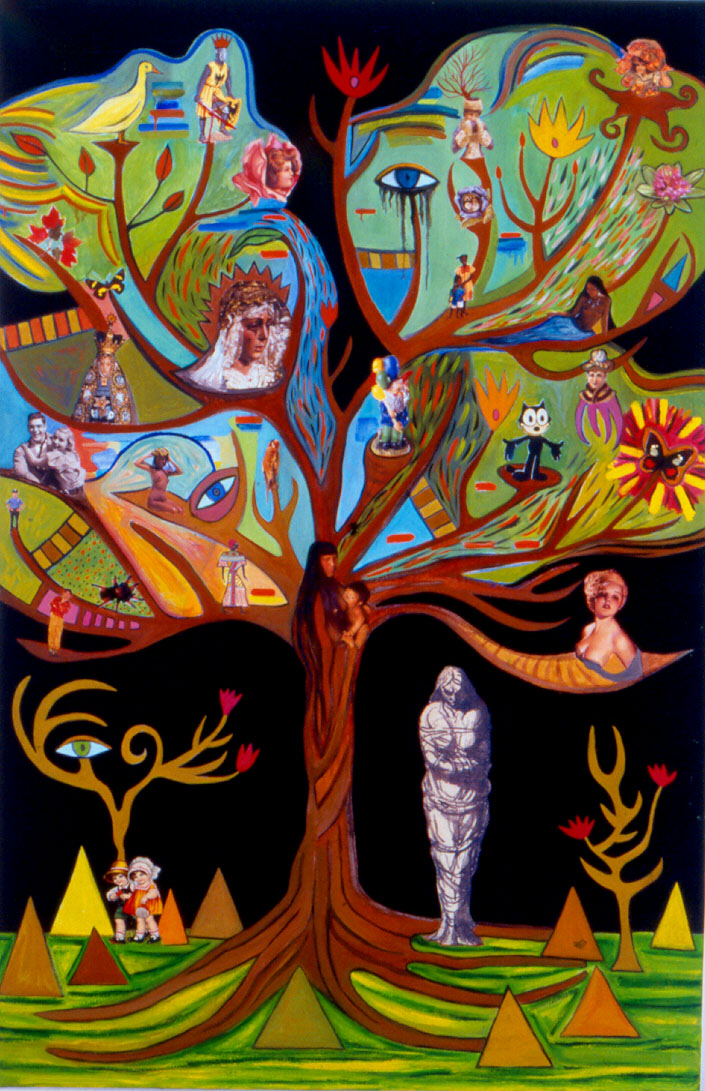

From the series, Susan Bee, “Philosophical Trees,” Bound and Unbound, 2004, 58” x 38’’, oil and collage on linen. Collection: Arlene Stein.

Well, as you say, the viewer is free to read into the artwork whatever they are seeing that day, and so, upon that word, I will venture something of an impression, or, dare I say, an interpretation. This is about the series “Philosophical Trees.” There’s so much more here than meets the eye. These paintings, these populations, are not unlike the rose-windows of sacred houses, I mean in that they present us with a mystery, with a “subliminal,” and this particular mystery has, of course, to do with these trees. The answer is not always in the eye, or else not immediately, it’s ironic that when we speak of the sense of something we are invariably going beyond the stuff of the senses and into the realm of perception, where the sense we are after lies. After studying this series of paintings, it occurs to me that I am not seeing “trees” so much as “tree structure,” and so these trees become, for me, trees of Porphyry. And in this sense, in this series, I see depictions of relation and reconciliation. These images, with which you populate these branches, they are, it seems to me, as ready-mades for you — but I don’t think you turn them on their proverbial heads, rather I think you give them reconciliation, which is to say you give them back their commonality, you return them to their noun, or, to their home. These are indeed “philosophical” trees.

So here we are in February 2012, and, looking back on 2011, it is remarkable your series of activities! There was in March, at the Janet Kurnatowski Gallery, in Greenpoint, NY, a showing of your daughter’s photographs, Emma Bee Bernstein: An Imagined Space, and in May there was your show Recalculating: New Paintings (which featured 32 new paintings!) at the A.I.R. Gallery in DUMBO, and in November at the Brodsky Gallery at Kelly Writers House at the University of Pennsylvania, there was a showing of prints from a series entitled “The Holocaust” by your father, the artist Sigmund Laufer, at which you and your husband, the poet Charles Bernstein, introduced the works and talked about the representation of the Holocaust in art. In November, the 25th-year anniversary edition of M/E/A/N/I/N/G Online #5, coedited with Mira Schor and including 83 artists, poets, and art critics, was published. In addition, you have been teaching at the School of Visual Arts and the University of Pennsylvania. And we see that this month, February, on the 23rd you are speaking at the School of Visual Arts in New York City about your work. Is there anything else you can let us in on at this time . . . are you at work on another series of paintings . . . what can you let us in on?

My next book project is Fabulas Feminae, a collaboration with Johanna Drucker. We are putting together a book about famous historical women including Cleopatra, Elizabeth I, Hildegard von Bingen, Billie Holiday, and many others. I have made 25 images and Johanna is writing the text and designing the pages.

I am speaking at a conference on feminist art, activism, and pedagogy, on April 5, 2012 at Parsons. I am also working on a series of new paintings for an upcoming solo show at Accola Griefen Gallery in Chelsea, NY in May 2013. There will also be a show of Emma Bee Bernstein’s Polaroids at the Microscope Gallery in Bushwick, NY, in May 24-June 25, 2012.

Thank you, Susan Bee.

Copyright © 2012 Susan Bee & Gregory Vincent St. Thomasino

Susan Bee

Susan Bee at the Electronic Poetry Center